The year was 1854 when two young riders pulled up outside Henry Van Sickle’s blacksmith shop, astride a single horse.

Their arrival at Van Sickle’s station wasn’t all that unusual — “Van” (as locals knew him) was an in-demand blacksmith and wheelwright, and his trading station had become a popular stopping place for passing-through emigrants.

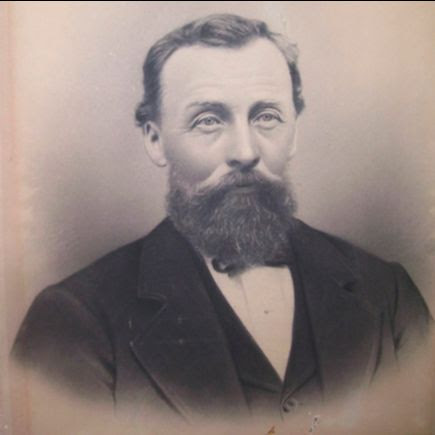

What was unusual, however, was the mission of the two riders. Young David R. Jones and his even younger companion, Frances Angeline Williams, weren’t interested in Van’s assistance as a blacksmith, but rather his help as Justice of the Peace. They’d just eloped together on horseback, and wanted “Van” to marry them.

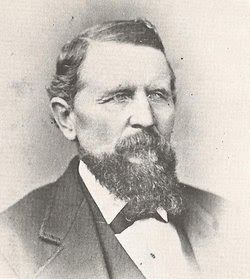

Frances was a native of Pennsylvania who’d come west with her family in a wagon train, arriving in Carson Valley during the fall of 1853. David had been born in Wales in 1830, emigrating initially as a child with his family to Wisconsin. David, too, had followed his dreams west to Carson Valley in 1853 as a member of the same wagon train as the Williams family, and was now living and working on the ranch owned by Frances’ father*, William T. “Billy” Williams.

David was 25 years old when he rode up to Van Sickle’s blacksmith shop that fateful day. Frances, on the other hand, was just 15. And they hadn’t asked her parents’ permission to get married.

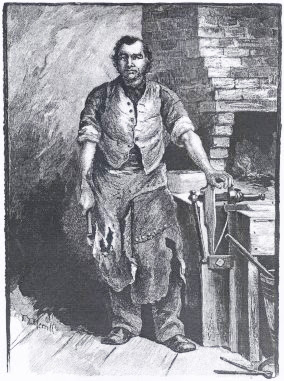

As later writers have recounted the tale, “Van” was hard at work at his forge when the eager young couple rushed in. Still clad in his leather blacksmith’s apron and rolled-up shirtsleeves, Van Sickle obliged with the briefest of ceremonies. Clapping one meaty hand on David’s shoulder and the other on Frances’, he solemnly proclaimed: “As Justice of the Peace of this township, I pronounce you man and wife under the law of the Territory of Utah.”

That was it. They were married.

It was the first settler marriage ever performed in Carson Valley, at least according to local legend. (Small pause for a word of caution: when it comes to “firsts” like marriages and babies, there can often be room for dispute! But that’s how local legend tells it.) And the wedding wouldn’t be Van Sickle’s last. In August, 1857, Van Sickle also “stopped branding cattle long enough to perform the marriage” for Elzy Knott and Mary Harris.

There’s just one small factual hiccup giving later historians pause about the long-ago Jones wedding story: Henry Van Sickle probably wasn’t actually a J.P. yet in 1854. It wasn’t until Carson County, Utah Territory was formed in September, 1855 by Orson Hyde that Henry officially became a judge, as nearly as we can tell. Prior to that, although J.P.’s did exist, their authority was limited to handling court cases. With no authority for anyone at the time to perform weddings, emigrant marriages were sometimes accomplished by written “contract” or by stretching the fictitious jurisdiction of an eastern J.P.

Still, the story of the Jones’ wedding is so detailed there’s likely some truth to the tale. Perhaps the young couple thought Van Sickle had the power to marry them, and Van simply tried to oblige. Maybe later tellings got the year wrong and the marriage took place in 1855, after Henry really was a Justice of the Peace. Or maybe the well-respected Van Sickle was simply the closest thing anyone had to a J.P. in those early days, and local folk never questioned the well-intentioned marriage attempt.

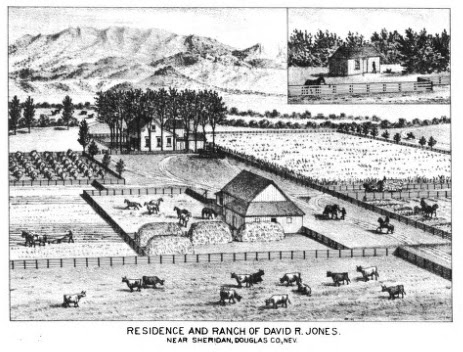

However it happened, if the oft-repeated story about the early wedding is true, newlyweds David and Frances must have had quite an interesting conversation with her family when they finally returned home to the Williams ranch! But any hard feelings were apparently soon forgiven. David would later purchase the Williams ranch in 1857.

Over the years, the couple prospered. David was (or at least, as he claimed to be) the first to plow the ground with an ox team near Genoa, and he soon began hauling hay and grain to Virginia City. But the early years of their marriage were filled with the dangers and difficulties of early pioneers. He would later recall: “We hid in the willows at night, [my] wife and I, because the Indians were hostile in those days and we feared for our lives.”

The couple’s first son, John R. Jones, born in 1855, was reportedly the first white male child born in Carson Valley. All told, David and Frances would go on to have a total of eleven children. One of those children, daughter Sarah, grew up to marry Lorenzo Smith of Washoe City, a tale recounted in this earlier story. (Daughter Sarah was laid to rest at the Washoe City Cemetery in early 1894.)

The Jones ranch grew, and by 1882 was valued for tax purposes at $3,500. David also evidently developed a passion for fine horses. In 1878, the newspaper reported the price for breeding services from his “noble-looking” stallion, Westfork.

David Jones was an active member of the local community, officiating as a judge of elections at the Mottsville Precinct in 1880, and serving as a Douglas County commissioner in the 1890s. According to some accounts Jones also became a prominent and well-respected member of the Mormon Church — although in actuality, he’d broken ties with the LDS church. Instead, Jones may have been affiliated with the Re-organized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when that movement emerged in the 1870s, though even the nature of his association with that group remains unclear. In any event, Jones was listed as a “minister” at the marriage of John Boston and Nettie Jones in March, 1872, and was kindly referred to as “Rev. Jones” in February, 1898 when he officiated at the funeral of Mrs. Mary Gilman.

Frances passed away in 1909, with seven of her 11 children still surviving her. Five years later, David was applauded as the oldest still-living Nevada pioneer at the state’s 50thanniversary celebration. He died that same year, 1914, at the age of 85. David and Frances Jones are both buried in the historic Genoa Cemetery.

* William T. Williams is identified as Frances’ father in Sam P. Davis’s later History of Nevada (Vol. II), but according to letters in the possession of descendants, her real father was actually David Williams. It’s possible that William T. Williams was an uncle.

Special thanks also to the Douglas County Historical Society for the wonderful pair of photos of Frances and David Jones for this story, and the account of their elopement from the reminiscences of Robert A. Trimmer, a typescript in the Historical Society’s Van Sickle Library collection. A similar story about the Jones wedding was told by Owen E. Jones in the Record-Courier of September 4, 1925. David Jones’ account of hiding in the willows was reported in the Record-Courier of February 5, 1909, and his land purchase from “Bully [probably Billy] Williams” was in the Genoa Courier, December 19, 1902. The account of “Rev.” Jones conducting the funeral of Mrs. Gilman is from Genoa Weekly Courier, February 11, 1898.

And just a quick acknowledgment: I am so thankful for the help of local historians who know so much more and so freely share! So, many thanks to one local historian in particular (who prefers to remain nameless) for the great information about the date of Van Sickle’s election as Justice of the Peace, various early marriage hurdles and work-arounds, and David Jones’ still-not-quite-clear connection with the Re-organized Mormon Church.