It was going to be the “War to End All Wars.” But when America entered the dreaded conflict overseas in 1917, local draft boards all across the nation were forced to make awful decisions: choosing which of their community’s young men should be sent off to fight.

Here in Douglas County, Nevada, local County Clerk Hans C. Jepsen became one of the men tasked with service on the Draft Board. They did it the fairest way possible: a lottery was organized, so the men to be drafted would be chosen at random.

Imagine Jepsen’s horror when the name that he picked was that of his own son, Earl.

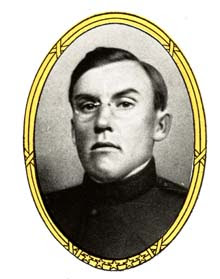

Two other men were in the room when Earl’s name was drawn. According to family lore, they both urged Hans to simply put his son’s name back and draw again. Perhaps they knew that Earl wasn’t a likely candidate for the military because his eyesight wasn’t good. Or perhaps they sympathized with a father’s guilt in sending his own son off to war.

Whatever their reasoning, the honorable Hans C. Jepsen refused. His son Earl’s name had been chosen, and that was that.

The Army, however, wasn’t so sure. Earl’s poor eyesight was indeed a stumbling block, and they repeatedly refused to induct him. But Earl kept presenting himself. He wanted to serve his country, he said. And eventually, the Army relented.

Earl enlisted on June 26, 1918 and was assigned to the Infantry, and by August had been sent overseas to the war zone in France. In late September, he was assigned to Company B of the 308th Infantry (part of the 77th Division), just in time to march with them into the Battle of the Argonne Forest. During this lengthy battle, Earl’s company became separated from the rest of the Allied forces and was surrounded by German forces. (The 554 men in these units would later become known as the “Lost Battalion.”)

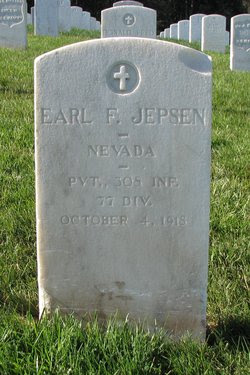

Earl was assigned as a runner to the battalion’s field headquarters, a job so dangerous it was considered a suicide mission. Earl was killed by sniper fire October 5, 1918, while on patrol. Just five weeks later, on November 11, the Armistice was signed, ending the war.

Earl was 26 years old when he fell on the battlefield. His body was buried initially in France, along with other American casualties. Some three years later, thanks to funds raised here at home, his remains were brought home again to the States. He now rests at the Presidio in San Francisco.

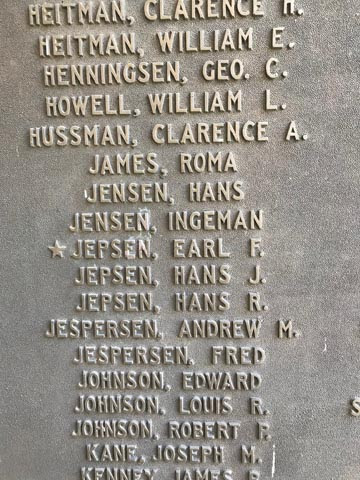

At the old Courthouse in Minden is a brass plaque, honoring those from Douglas County who served during World War I. And as you will see if you visit, Earl isn’t the only Jepsen to have served during this “War to End All Wars”: his brother, Hans R., and cousin, Hans J., also are honored on the plaque. A simple bronze star beside Earl’s name signifies that he gave his life for duty.

This Veteran’s Day, we hope you will remember him — a local boy who did what he felt he must to serve his country.