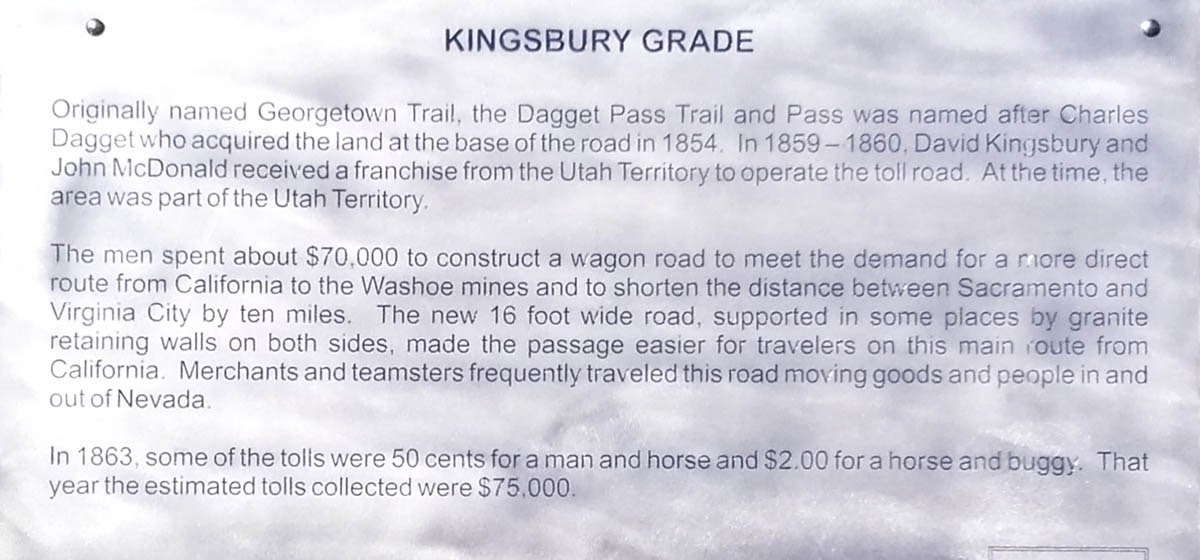

Few people ever stop to read the Historic Marker for Kingsbury Grade. Perhaps that’s because the marker isn’t actually on today’s Kingsbury road at all, but rather on Foothill, tucked between Mottsville and Muller Lanes. But this small sign marks a fascinating and important early site: the original jumping-off spot for emigrants bent on taking the Daggett Pass route to the goldfields of California.

It wasn’t everyone’s first choice as a route, though.

Long before white men arrived, this trail began as a simple Washoe footpath up to the lake. At the height of the Gold Rush, Georgetown (Calif.) boosters began working to press the track into service to draw emigrants to their community. These enterprising townsfolk sent “salesmen” over to the Eastern slope to divert would-be miners to Georgetown, instead of the usual Placerville route. Hired hawkers vigorously promoted what soon became known as the “Georgetown Cutoff,” assuring emigrants (falsely) that it would slash their trek to the goldfields by 50 miles or more.

But the Georgetown Trail or Cut-off (as it then was known) remained a barely-improved footpath. In July, 1850, emigrant Edmund Hinde took one look at the steep, rough climb and decided to stick with his original plan to follow the more-established Carson Canyon route. “On looking at the [Georgetown] road, we concluded to keep to the old one,” he sighed.

The flat at the base of the trail did make a fine place for a party, however. Many eager gold-seekers who opted for the difficult Georgetown route simply abandoned their wagons, guns, and other personal possessions at the foot of the trail and forged ahead as “packers.” Those piles of discarded belongings became a temptation to mischief. In his 1850 diary, Abner Blackburn recounts how the boys of Mormon Station would go on a “spree,” setting fire to piles of abandoned wagons, cutting up discarded harnesses, bending guns around trees, and “run[ning] amuck generally.”

In 1852, J.H. Scott and his brothers settled at the foot of the trail, building a small log cabin there. The location was a good one: it had a spring, and was only a few miles south of Mormon Station. The following year, the Scotts sold out to Dr. Charles Daggett. Born in Vermont in 1806, Dr. Charles Daggett had come west in 1851. According to local lore, Daggett brought two African-American slaves with him to Carson Valley, a woman and her little boy, thus becoming one of the very few early slave-holders in the valley.

Daggett and his companions settled into the log cabin at the base of the mountain. His land claim, filed May 12, 1853 for 640 acres, was among the earliest in the “First Records.” In 1854, Daggett solidified his claim by having a survey made of his property. A graduate of Berkshire Medical College in Massachusetts, Daggett was the first doctor in the region and, by some accounts, the first in all of future Nevada. He also held public posts in 1855 as Carson County Assessor/Tax Collector as well as its prosecuting attorney. Not surprisingly, the trail up the mountain near his home, the creek that flowed down the mountain, and the pass above all soon took his name.

And a lucky thing Dr. Daggett’s presence was for Judge Orson Hyde, who arrived at Daggett’s cabin with frostbitten feet and legs in December, 1855, after crossing the mountains in the snow. Aware of the dangers of rapid-thawing, Daggett chopped a hole in the ice on a nearby stream and told Hyde to soak his legs. He then rubbed Hyde’s frozen legs with turpentine and bandaged them in soft cotton.

For several more years, Daggett Trail remained practical only for travelers on foot or with pack-horses or mules. Surveyor George Goddard, visiting in 1855, noted that although the trail from top to bottom was just under four miles, the drop-off was steep and “a false step would precipitate one into the rocky canyon 500 feet below.”

Then about 1856, a Genoa merchant named William Nixon took an interest in improving the Daggett route. A Mormon from St. Louis, Nixon had arrived in Genoa that year from Salt Lake with a load of goods with which he opened a store at Mormon Station. Before returning to Salt Lake in ’57, Nixon had the trail over Daggett Pass improved so that wagons carrying goods had an easier time of it.

But “easier” was a relative term. In 1859, Capt. J.H. Simpson gave his own skeptical opinion that a great deal of work would be necessary to make the route truly passable by wagons.

For the most part, the Daggett route remained essentially a pack-mule or horse trail. But the Comstock Lode would soon change all that.

Two ambitious businessmen (D.D. Kingsbury and John M. McDonald) saw huge profit potential in improving the road (and, of course, charging a hefty toll) to serve wagons laden with goods for the mines of Virginia City. They constructed the “Kingsbury & McDonald Toll Road” over Daggett Pass, beginning in the winter of 1859 and finishing in August, 1860.

It was an important step not only for Kingsbury and McDonald, but for Carson Valley itself. Writing in November, 1859, Richard Allen predicted the road project would “facilitate communication, reduce freight, and add materially to the advancement of Carson Valley.” And right he was.

Stay tuned for “Part 2” of the Kingsbury Grade story!

_________________________

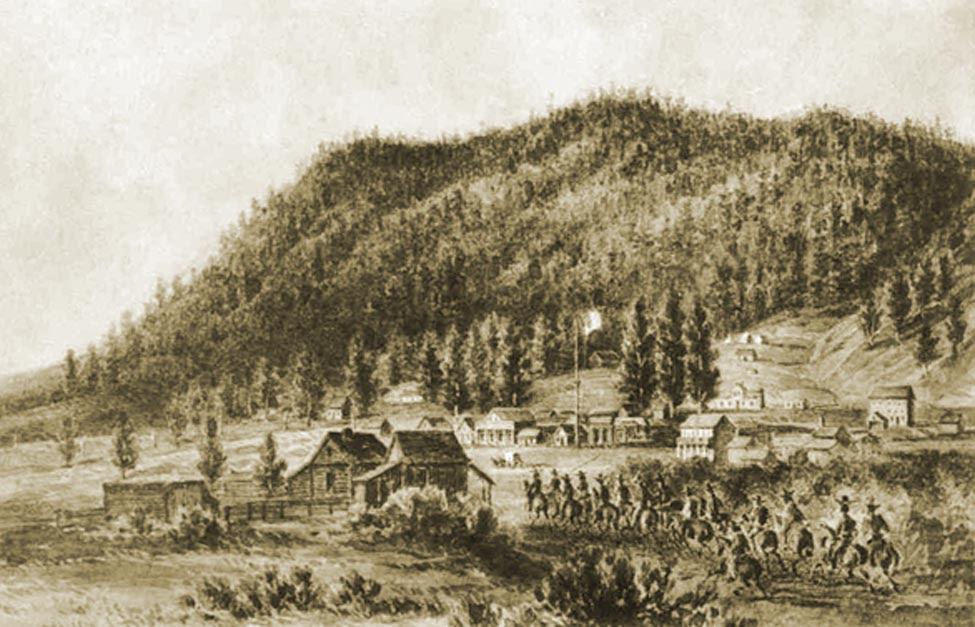

Many thanks to the Douglas County Historical Society for permission to use the wonderful image at the top of this post. It’s of Kingsbury Grade circa 1885-1895 taken with an early model Kodak camera, which produced these circular images.

_______________________________________

Karen Dustman is a published author, freelance journalist, historian, and story-sleuth. For more about Karen, her books and other fun stuff she’s written, check out her author website: www.KarenDustman.com.

________________________________________