Even before the Kingsbury & McDonald toll road was completed, the quasi-passable track began to attract attention. A telegraph line for the Humboldt & Salt Lake Telegraph Co. was strung along this route in late 1858, connecting Genoa with Placerville. And beginning in April or May, 1860, Pony Express riders began following the Kingsbury Grade trail, before completion of telegraph lines a few months later made their work obsolete.

When Kingsbury & McDonald’s new wagon road was officially completed in August, 1860, it was seven miles long but reportedly chopped the distance from Genoa to Placerville by some 15 miles, saving travelers a precious day’s travel.

Writer Richard Allen marveled at the workmanship of the new road, describing it as a “most excellent road” winding over “seemingly impassable heights.” A reporter for the Sacramento Daily Union similarly effused in June, 1860: “The road-building by McDonald & Kingsbury through Daggett’s Pass is pronounced by those we have seen who have passed over it, the best on the Pacific coast.”

The roadway of the new Kingsbury route averaged a luxurious sixteen feet in width — a vast improvement over portions of the Placerville road in El Dorado County, where sharp turns planked to a width of just eight feet made it difficult for six-mule teams to “keep the wheels on the timber.”

Kingsbury and McDonald received a Territorial franchise for their toll road in 1861. The initial toll for a wagon drawn by four horses making a round-trip from Shingle Springs to Van Sickle Station at the foot of old Kingsbury was $17.50. That hefty sum represented more than four days’ wages for a humble miner. Even so, writer Richard Allen dubbed the new toll rate “reasonable.”

The Kingsbury route soon drew away many of the westward-bound travelers who had previously crossed through Hope Valley and over Luther Pass. In addition, with Virginia City at its height, pack train operators bringing supplies eastward for the Comstock mines found the route profitable in the early 1860s. Some of those early packers settled in and became Nevada notables. Bob Fulstone, for example, a well-known dairy rancher near Carson City, recalled “packing mules” over Daggett Pass as a teenager. And A. Schwarz, cheerful proprietor of the popular Genoa Brewery, once ran a pack train from Sacramento to Virginia City in his younger days, also probably following the Kingsbury route over Daggett Pass.

At the very foot of the new Kingbsbury trail, Henry Van Sickle already had an existing station that he’d erected in 1857. This offered several amenities for emigrants and teamsters: a bar, a hotel, a blacksmith/wheelwright shop, and a store. Van Sickle quickly embraced the new Kingsbury route as good for business. He not only helped finance the new road but also served as its first toll-master. Although we don’t know much about the original toll house, we do know it had a brick chimney, as that fell down during an earthquake in June, 1887.

About halfway up the grade, travelers could also find another way-station, called “Peters Station.” Here Richard Peters and his wife, Elizabeth, kept a three-story hotel where teamsters could enjoy a good, hot dinner and get a restful night’s sleep for themselves and their horses before attempting the rest of the climb.

The new Kingsbury toll road didn’t keep its competitive advantage for long, however. In November, 1863, the Lake Bigler Road was completed and began siphoning off traffic. This new road ran from Friday’s Station (then “Small & Burke’s”) on the south shore of the lake through Spooner’s Station and down Kings Canyon to Carson City. It not only crossed the Sierra some 200 feet lower than the Kingsbury-McDonald route but, more importantly, reportedly offered a slightly shorter trek to the Placerville road.

That didn’t mean that all travelers abandoned the new Kingsbury route, of course. And in 1866, J.W. Haines found yet another helpful use for it, building a mile-long box-flume to channel water down Kingsbury Canyon, later upgrading its original overlapping joints to an “abutting joint” model in 1868.

All told, the new Kingsbury & McDonald toll road cost its founders an astonishing $585,000 to build. And in 1863, after the Kings Canyon route opened as competition, Kingsbury generated only $190,000 in tolls. Even so, the new Kingsbury toll road continued to operate. By 1881, the History of Nevada would grandly claim that the Kingsbury toll road had “annually returned double its cost.”

Perhaps this was pure puffery. Financial woes eventually forced Van Sickle, who had helped to finance the road, to foreclose on his mortgage and he wound up becoming its owner. For a time, it continued to operate as the Van Sickle Toll Road. But in 1889, Van Sickle sold the roadway to Douglas County for just $1,000. It now became a free road; the local newspaper happily advised readers that “no toll will be collected in the future.”

The lack of tolls made a big difference for commerce over the Grade. In February, 1890, for example, ranchers in Carson Valley were able to supply Folsom’s logging camp at Lake Tahoe with beef, which they “hauled over the Kingsbury grade on hand-sleds.” And in 1894, a Sacramento hauler estimated the cost of delivery at a mere one cent per pound, compared with $1.25 per pound when the previous toll over Kingsbury was $22.

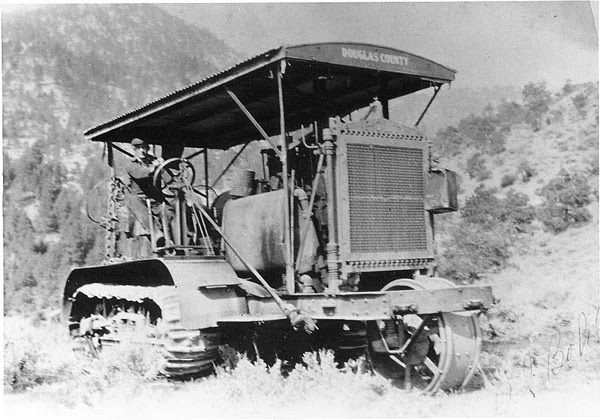

Given the road’s unpaved surface, maintenance needs were constant. In summer, horsedrawn carts would sprinkle water along the roadway to settle the dust. In winter, sleds were used to pack the snow down as a roadway.

Horrific accidents on the steep grade were also common. In June, 1890, a man named Green lost his brake while descending Kingsbury grade with a 6-horse team. Although the incident made the news, the Genoa Weekly Courier just calmly reported: “the wagon ran off the grade, causing quite a smash-up.” The following year, teamster Louis Lenwick was bringing a load of shingles down Kingsbury grade from Hobart with a 4-horse team when he hit an icy spot at the “first bridge above the Farmers’ Mill.” Luckily Louis got off with just a broken rib and a dunking in the creek.

Then in May, 1892, someone made the bad decision to continue tugging an engine up Kingsbury Grade with a 12-horse team during a heavy snowstorm. The engine was destined for use at a logging camp near Meyers, but wound up being dumped off onto its side when the wagon’s wheels “dropped into a hole that was covered with snow.” The team and driver came out alright, but the engine later had to be rescued.

*Hope you enjoyed the story so far… To read Part 1, click here. We plan to add Part 3 to the story later!

Header photo (used courtesy of Douglas County Historical Society – thank you!) is Old Kingsbury Grade, circa 1895. Note what appears to be a flume at right center of that photo.

_______________________________________

Here are a few great personal memories of old Kingsbury Grade “back in the day,” from our readers:

“My mom said they made movies on that road. I remember the hairpin turn punctuated by the lone pine tree.”

“I can remember traveling up the grade, scared to death that my father would get close to the edge on a sharp turn with a corduroy surface, and we’d all go over the edge! And I remember how relieved we were to make it to the ‘piped’ spring [where we could] refill the boiled-out radiator.”

“Many of the young men (my brother and my husband among them) who belonged to Carson Valley’s 20-30 Club would go up to the Lake after their meeting, and they’d talk about coming home in the early morning via Kingsbury with the sun in their eyes.”

“The lookout point was constructed by the local Kiwanis Club, I think. It became more of a ‘necking stop’ than an actual scenic look-out.”

“When I was in high school, the road was still dirt and people from California driving Kingsbury Grade would hug the side that is against the mountain and you would have to go around them on the wrong side because they were scared to go near the edge.”

“I remember in winter they would close the road with just a couple of saw horses and a board. If the snow was not too deep we would just move the saw horses aside and just use it anyway.”

_____________