Old Yank’s Station has a cool anniversary coming up on Sunday, April 28th — 159 years, to be exact!

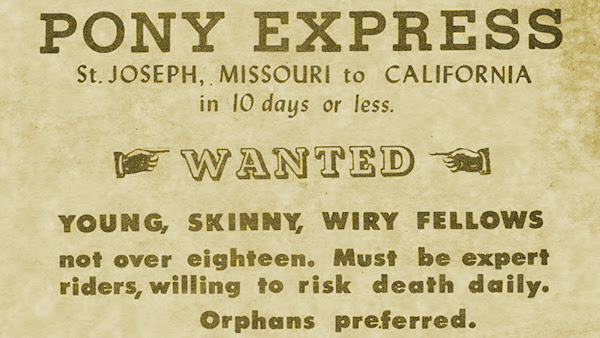

On April 28th, 1860, exactly 159 years ago, a young Pony Express rider named Warren Upson came flying in to change ponies, stopping for the very first time for his mount change at Yank’s.

The new road over Kingsbury Grade had just opened, you see, which offered a shorter route for the mail heading east to Genoa than on Upson’s previous rides. (On earlier rides, Upson had taken a longer route through Hope Valley and Woodfords.) Now, with the new Pony Express stop at Yank’s, Upson would only need to ride as far as Friday’s Station (today’s Stateline) before handing the mochila over to the next Pony Express rider.

Today, of course, they don’t call it “Yank’s Station” anymore. The site is now home to Holiday Market (formerly Lira’s), at the southwest corner of Highway 50 and Apache Avenue in Meyers. The Pony Express only stopped at Yank’s for a year and a half — until October 26, 1861. But Yank and his station had a fascinating and much longer history!

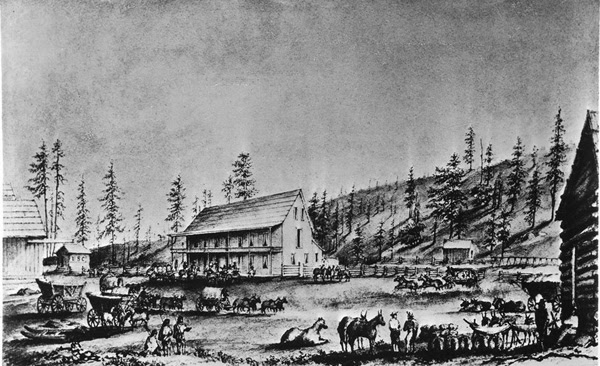

Ephraim “Yank” Clement had been the owner for less than a year when Upson arrived that April. The previous owner, Martin Smith, had settled there in 1851, rebuilding the trading station once after an early fire. By the time Yank Clement came along and bought it from Smith and a partner in 1859, the station was already a well-known trading post and stage stop. A telegraph relay station had just been added in 1858.

And Yank Clement brought his own bigger and grander ideas. After he purchased the station in 1859, he kept adding and expanding. Eventually his station was three stories tall, featuring 14 rooms, a general store, a blacksmith shop, and last but not least — twosaloons! It’s said that those quickly became popular with travelers not only for drinks, food and card games, but also a handful of ladies of dubious virtue who could be found there. Across the road, Clement added large corrals, and the station featured a large barn with stables for travelers’ animals.

Yank was a larger-than-life character who quickly became a local celebrity. He was a true Yankee indeed, claiming to have moved west from his native New Hampshire at the age of 40 and acquiring the station “at the instance of Chorpenning.” Yank would regale visitors with tales of his early adventures, which (supposedly) included a brief sojourn as a cooper in Cuba and service as a chaplain at the Battle of Bunker Hill — this last an amusing but thoroughly impossible tale for a someone born about 1817. Planned future improvements, he assured guests, would include a tree-house lookout for better views of the lake; a fish pond with water-spouting Cupid; and a brand new piano (pronounced “peeyan-er”) for his house. The warm and effusive host was said to accompany his narratives with “many amusing peculiarities of phrase and gesture.”

In the outpost’s early days, at least, the location was still a remote slice of the Old West. A California teamster named Grace got held up at gunpoint near Yank’s Station in November, 1865, while on his way home after delivering a load of goods to Dayton, Nevada. Five “foot-pads” with shotguns accosted Grace’s wagon near Yank’s Station, and the poor teamster was forced to hand over the entire $450 proceeds he’d earned for his trip.

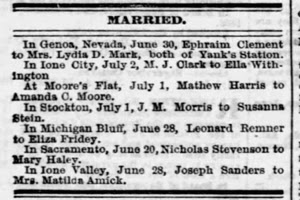

After almost a decade in business Yank acquired a bride, marrying Mrs. Lydia D. Mark in Genoa on June 30, 1868. The new Mrs. Clement became a strong partner in the hotel business, with visitors commenting on her excellent cooking and housework skills.

Tragedy struck the pair just a few short years later, however, when Yank’s hotel was consumed by fire in December, 1872. Among those who barely escaped with their lives were Yank, his wife Lydia, and a Mrs. Cleveland, the wife of a senator. Mrs. Cleveland suffered burns on her face and hands as she rushed out of the burning building, and Lydia Clement was said to have had her hair “singed to the roots.”

Perhaps as a result of this catastrophe, “Yank” sold his station to George D.H. Meyers in 1873. Meyers would later expand the holdings, purchasing nearby land, and began raising cattle there. The property would stay in the Meyers family for the next 30 years, and later was acquired by the Celio family.

Despite the sale of his original station, Yank wouldn’t abandon the hotel business, however. He soon built another hotel near Camp Richardson known as Tallac House, memorialized by famed photographer Carleton Watkins in 1876. This hotel was grander than ever, featuring a spring floor for dancing called an “emotional floor.” And naturally, given Yank’s personality, it was still commonly known as “Yank’s.”

A visitor in August, 1875 described the accommodations, which included a bed “at least four feet from the floor” and a single shared toothbrush “in a large pressed-glass tumbler,” thoughtfully provided for the comfort of Yank’s visitors. Clements and his wife set a good table, the writer confirmed (“I mean it — a real good table is theirs”), and described them as “bustling around as usual and doing all in their power for their guests.” Another guest remarked cryptically that he and his friends had managed to procure an early breakfast by “ventur[ing] to brave the small explosive dangers of Yank’s dining hall” — possibly a reference to being cornered by Yank with a story.

Yank was described as “the most obliging old coon in the world, [who] flies off here, there, and everywhere all day in the interest and comfort of his guests.” Mrs. Clement was a “first-class housekeeper,” keeping the hotel running smoothly along with help from her niece, a Mrs. Rogers. And Yank was said to out-do himself for guests: “If you want his house, team and wagon, it comes marvelously at your order; and if you order saddle horses or boats he makes a spring and a whiz and you are equipped.”

For a time, Yank Clement also served as local justice of the peace, much to the amusement of those in his courtroom. During the trial of one case, Yank fell sound asleep and “began snoring like a house afire.” When roused from his slumbers so the evidence could continue, Yank responded tartly: ‘That’s all right. I knew all about the darned case [before] it came into the court [and] made up my mind about the merits long ago.” In another instance, one man was trying to sue another for an unpaid debt. “Well,” Yank inquired, “Did you have a talk with him about the matter? And he wouldn’t give you no satisfaction?” No, Yank was assured, the debtor had refused to pay. “By jingo!” he erupted. “If you couldn’t do nothin’ with him, how in blazes can you expect me to do it?”

Clement’s Tallac House was sold about 1880 to Elias “Lucky” Baldwin, who would later build an even grander Tallac Hotel there. As for the original Yank’s Station in Meyers, it was finally “done in” for a third time by fire in 1938 — along with much of the surrounding community of Meyers.

So this April 28, it’s only fitting to consider a pilgrimage to the site of old Yank’s Station in honor of this 159th anniversary. Imagine young Warren Upson, tired and cold, making his hurried change of ponies and dreaming of a quick stop at Al Tahoe and the warm fire ahead at Friday’s Station. And imagine Ephraim “Yank” Clement standing in the door of his original Yank’s Station, waving good-bye and wishing Upson god-speed on the road ahead.