So, how did Jonas Winchester get to California?

Ah, that’s a story in itself! (And if you missed Part 1 of Winchester’s wild and crazy story, ![]() here’s where to read it!)

here’s where to read it!)

The eighth of 13 children, Jonas Winchester entered the world on November 19, 1810 in Marcellus, New York. At roughly age 16 he was apprenticed to Adolphus Fletcher, printer of the Jamestown Journal, a local weekly paper.

But by the time he was 18, Winchester determined to set off for adventure. He made his way to New York City, where he arrived (as he later put it) “a stranger, without friends, acquaintances, or recommendation of any kind.” He was sure a better life awaited him. “Destiny calls and I must follow,” he wrote to his mother in September, 1829.

Despite his lack of connections in the City and with only 2-1/2 years of apprenticeship under his belt, Winchester managed to land a job as a compositor for two New York City newspapers. But the pay proved meager. Wages for compositors were so low, in fact, that in September, 1830 Winchester moved back home to Western New York, where he took a job with the Fredonia Censor.

But the lure of the big city hadn’t left him. He returned to New York City again in the Spring of 1832. And in 1833, Winchester eventually landed a publishing job with Horace Greeley, likely due to his friendship with Frank Story, Greeley’s partner. Winchester had a certain “larger than life” aura about him, and perhaps a certain amount of moxie helped win him the position. Somewhere in his youth Jonas gained the nickname “General” Winchester, a military honorific with “no foundation in fact,” as his descendants would later admit. (It may have been a bit of a family joke; brother Herman went by “Colonel.” And the oldest brother in the family dubbed himself “Patriarch.”)

Horace Greeley himself was a relative newcomer to New York City, too, having arrived in late 1831. By the time Winchester became an associate, Greeley had already launched and lost the short-lived Morning Post – a publication which cratered within three short weeks of its January 1, 1833 debut. A few months later another tragedy struck Greeley — his original business partner (and Winchester’s friend), Francis V. Story, drowned suddenly in July 1833.

Story’s death presented a fortuitous opening for Winchester, who stepped in to become Greeley’s partner. In March, 1834, Greeley and Winchester launched a new publication called the New Yorker — a “large, fair, and cheap weekly folio” based on Ann Street, New York, dedicated to literature with a sprinkling of news. Greeley handled the newspaper’s editing, while Winchester did what he did best — promotion — taking charge of the profitable “jobbing business” (contract printing). Before long Winchester would solidify his fortunes by marrying Story’s sister, Susan — the wedding taking place on Winchester’s own 25th birthday, November 19, 1835.

Although launched with only a dozen subscribers, the New Yorker’s circulation eventually reached 9,000. But it never became a rip-roaring financial success. Instead, it took “a terrible struggle on the part of its proprietors to keep it alive.” Greeley and Winchester eventually dissolved their partnership in September, 1836. Winchester carried on “job printing” on his own, then tried to make a profit by reprint literature from abroad. But he got himself deep into debt (thanks to what one observer called his “careless and venturesome way”), and about 1844 was forced to declare bankruptcy. The timing couldn’t have been worse for a new family man; Winchester and his wife, Susan, now had two children: Frank S. Winchester, born in 1840, and Julia, born 1844.

Eager for a new start, Winchester was bitten by the “gold bug” when glittering tales of California gold began circulating in late 1848. It was a chance to redeem his fortunes!

News of the California gold strike at Sutter’s Mill was all over the newspapers in New York. Reports circulated that some $2 million in gold dust was already sitting in San Francisco, just waiting for transportation to the East. Despite stories of earlier “disturbances” in the mining districts, the New York Tribune assured its readers that “excellent order [now] prevails.” As for tales about “thousands starving,” those rumors were simply “greatly exaggerated,” the press reassuringly reported.

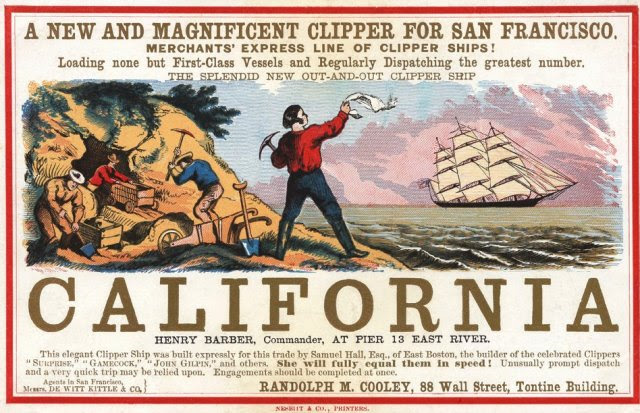

Winchester learned of a three-masted “half-clipper” ship leaving New York and headed for California. She was called the Tarolinta, Indian for “floating rose,” owned by the Griswold Brothers of New York and captained by William P. Cave. With a capacity of 549 tons and a crew of 27 (some 20 of them African-American), the Tarolinta expected to carry both a lucrative load of cargo and roughly a hundred passengers to the gold fields. Winchester was determined to be among them, and quickly booked passage.

The Tarolinta was initially scheduled to depart from New York harbor on December 28, 1848. But not enough passengers signed up at first, so the date was postponed until January 9, 1849 in hopes of recruiting additional passengers. Then arrangements for additional freight to be delivered to South America caused the date to be pushed off yet again, to January 13. You can only imagine Jonas Winchester tapping his toes in frustration.

The morning of the 13th of January, 1849, dawned clear and cold. A huge snowstorm had dumped as much as three feet of snow on the streets of New York. Passengers were instructed to board promptly at the pier at the foot of Wall Street. And finally the Tarolinta pushed off.

Champagne was passed around as the ship was guided out of the harbor by pilot boats. She was heavily laden indeed. Freight was lashed into tall piles on deck, and included barrels of provisions, small boats, and “house frames.” Total passengers came to 125 – more than originally planned.

Winchester was among the passengers happy to turn his face toward California. He still owed thousands of dollars to his creditors. But he left behind his wife and two children.

Ads for passage on the Tarolinta had promised travelers “superior accommodations.” In fact, however, space was minimal and the food less than ideal. One passenger reported a dozen men were sharing a 22-1/2 x 7-1/2 foot “stateroom” that was “nearly filled up with our trunks, chests, and other baggage,” leaving meager sleeping spots just three feet apart.

Passengers, of course, eagerly discussed their possible prospects in the California goldfields. At least 15 separate mining “companies” were organized aboard the ship, each with a name and its own distinctive pennant. Jonas Winchester was no doubt one of the founding members of the ten-person “Leyon Winchester & Co.”

Fellow printers James B. Devoe and Daniel Norcross of Philadelphia (later manager of the San Francisco New Age) were also included among the passengers. Others included an “accomplished Oriental scholar” named Caleb Lyon, and Dr. J.C. Tucker, whose diary of the journey would eventually be published.

A physician named Dr. Nelson whiled away the hours at sea by conducting “experiments on the porosity of glass” — a misguided effort to see if submerging a hermetically-sealed glass tube to 89 fathoms would cause water to penetrate the glass itself. (Not surprisingly, the answer was no. But Dr. Nelson nevertheless shared his “experiment” with the world in an issue of Scientific American.)

The Tarolinta reached Rio in February, 1849, a happy milestone for the passengers as the stop offered fruit and “lots of mint juleps, and porter-house beef steaks.” These were quite a treat indeed after the shipboard fare. One passenger filed a report from Rio describing typical shipboard fare as a “curious concoction of mouldy bread and frozen potatoes, boiled down in salt water” and “apple fritters, about two inches thick, eighteen inches around, and weighing four pounds and a half each.”

As they continued on around the Horn, passengers aboard the Tarolinta endured stormy weather, extreme cold, poor fare, and personality clashes. Perhaps predictably, disputes arose over food rations, hammock space, bathing water, petty thievery, and other matters. Some led to fisticuffs.

By and large, Captain Cave tried not to intervene. When two passengers got involved in a brawl on the poop deck, the Captain merely told them to move their dispute down to the quarterdeck so neither would fall overboard. But when eager passengers began trying to chop up barrel staves to make tent stakes in preparation for their anticipated mining adventures, the captain finally asserted his authority and stopped them. Barrel staves were a precious cargo.

Some would later say Cave was a “cold, ruthless and stubborn man, whose odious character would become clear to all as the voyage unfolded.” Others called him “big and blustering.” More likely he was just overwhelmed by trying to corral such a large group of eager, unruly passengers.

After 174 days, the Tarolinta finally sailed into San Francisco harbor on June 29, 1849 (July 6, 1849, according to other sources), much to the relief of all aboard, the captain no doubt included. But there they found the dock space completely occupied. They were forced to drop anchor in the harbor and hire rowboats to get their parties and goods ashore. And goods there were, a-plenty! Operators of the “Russian Store” at San Francisco soon advertised the arrival of assorted silk shawls, handkerchiefs, ladies’ fancy cravats, ribbons, plaid silk, buck gloves, silk scarves, plus a “superior assortment of cigars,” all courtesy of the Tarolinta.

Stepping on shore that summer of 1849 put Jonas Winchester among the very first eager members of the California Gold Rush. He and his associates briefly tried their hand at mining on the North Fork of the American River. They purchased steam-powered equipment, and built dams and even roads. But the fall rains washed all of their hard work away.

By the winter of 1849 Winchester turned back to what he knew best, securing a post as editor and part-owner of the Pacific News – one of the first San Francisco newspapers. In May, 1850, Winchester also took over the appointment of H.H. Robinson, California’s first State Printer. The government printing contract offered plenty of steady work, but payment by the State was issued in semi-worthless warrants, making it difficult for Winchester to meet his obligations. He resigned the post in March, 1851.

The Pacific News folded in 1851, the victim of several fires. But Winchester was still intrigued by mining, and convinced that “greater things were in store for him.” He moved to Grass Valley, where it’s said he built the first sawmill and quartz mill in the vicinity, and acquired interests in mining companies.

Meanwhile, back in New York, Winchester’s wife, Susan, was suffering from consumption (tuberculosis). Winchester’s California mines had failed to produce the great returns he’d hoped for. So Winchester decided to return to New York.

Susan died in Brooklyn in February, 1855, at just 43 years of age. Sometime after 1855 Jonas wed widow Margaret Bartholomew Brown in New York. Margaret was a supporter of women’s suffrage and an associate of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. But apparently that marriage did not last. In April, 1869, Winchester married a third time, wedding Laura Karner. Their first child, Ernest, was born in 1870 but died in infancy.

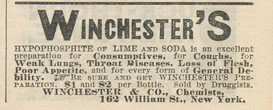

Winchester had launched a patent medicine business, “Winchester’s Hypophosphites” — proudly putting his own signature on the label. The endeavor helped him make ends meet, bringing in an estimated $3,000 per year. But he was still eager to try his hand at mining.

In the 1860s he acquired the Globe Gold & Silver Mining Co. and other mining interests in Monitor Canyon, in Alpine County. As early as 1867, Alpine locals were receiving letters saying Winchester intended to come out “next season.” And come out he finally did, moving to Monitor with wife Laura in 1871. They would have two children who were born there at Monitor.

So that’s how Jonas Winchester wound up in Alpine County. And that’s where our story picked up last time! (Here’s the ![]() link again, if you missed Part 1 of Jonas Winchester’s amazing story.)

link again, if you missed Part 1 of Jonas Winchester’s amazing story.)

Call it serendipity. But as luck would have it, Winchester’s 209th birthday was November 19th — just about the time this story came out in our 2019 newsletter. We hope you’ll light a candle to celebrate the birthday of the wild, wonderful, adventurous life of Jonas Winchester! What a life he had.