A Family Affair . . . .

Like all good mysteries, this one began with a tiny clue. An old newspaper from August, 1880 happened to mention a man who’d breathed his last at Walley’s Hot Springs. His name, we discovered, was Benjamin F. Seely. But who was Seely? Ah, and that’s where the twisting path began!

“Frank” Seely, it turns out, was a carpenter (or “joiner”) by trade. A native of Connecticut, he’d spent time in Shasta County, California before moving on to Nevada. In the years just before he died, he’d been working at the mines in Esmeralda and Mineral County, Nevada. Seely passed away at just 65 years old, suffering from typhoid and jaundice – ailments that even Walley’s renowned medicinal springs weren’t able to cure.

And here’s where our story took a turn for the wild side. Digging further into Seely’s past, we discovered that in 1855, Seely had married a 23-year-old woman named Julia E. Glynn at a Shasta hotel.

Julia had been born in New York about 1832. She’d come west with her parents and brother; her father (a dentist) would wind up a city alderman near Sacramento. Julia’s 1855 marriage to Frank Seely seems to have ended rather quickly, though we haven’t been able to figure out exactly when. But for Frank Seely, severing ties with young Julia would prove to a thoroughly lucky thing.

By 1860 (five years after her wedding to Seely) Julia was already married for the second time – to a man named Aaron Spencer, who divorced her in December of that year. But Julia still didn’t give up on the notion of marriage. On November 4, 1867, Julia (now back to using the Seely surname) wed Nelson James Savier in Stillwater, Nevada.

And her third trip to the altar definitely didn’t prove to be the charm.

Nels Savier was the son of a good family. The oldest of five children, he’d helped drive the wagons when his father emigrated from Ohio in 1857. Father John Savier would become one of the earliest settlers in Ventura County, and was elected the first judge for the Hueneme District.

It’s unclear how Julia and Nels each made their way to Stillwater, Nevada, or how they were introduced. But what does seem to be clear is that at the time of their 1867 marriage, Julia was about twelve years older than her new young husband.

The couple took up residence in Carson City, where in 1869 Nels was employed as a telegraph operator. To make extra money he began selling life insurance and books, and he served as the “journal clerk” to the state legislature in 1871. He eventually opened a photography studio in Carson City, which his wife helped to run.

And most fatefully of all, he began selling Wheeler & Wilson sewing machines out of their home.

And here, a different Julia enters the picture. Julia Lake also lived in Carson City. Later accounts would suggest that she initially met Nels when she came to the Saviers’ home to buy a new sewing machine.

Julia Lake, too, was married – though not happily. We’ll skip her rather long back-story for now. But suffice it to say that Julia Lake was on her third marriage. Her current husband (Augustus Lake) had taken off for the fresh mining districts as much as a year earlier, leaving her on her own, with two young children to raise.

By mid-1870, Julia Lake and Nels Savier were carrying on an affair. Petite and attractive, Julia Lake was also much closer to Nels in age. Wife Julia Savier, by contrast, was by now portly, middle-aged and in poor health.

Secrets don’t stay secrets very long, especially in a small town like early Carson City. Wife Julia discovered her husband’s affair and in late spring, 1871, she confronted Nels. They argued. Nels stormed off.

But it was a pretty pickle he now found himself in, indeed. The pretty and probably destitute Mrs. Lake was pregnant with his child.

With a baby about to make its own existence obvious, the illicit pair couldn’t stay put in Carson City. So they hatched a plan. On a fine summer day in June, 1871, the pregnant mistress left Carson bound (ostensibly) for Virginia City. Savier left town that same evening, heading for Reno. They rendezvoused there in Reno and took off to Stockton together, where they settled cozily into a room at the Grand Hotel, registering as husband and wife.

Nelson seemed ready to make the move permanent, taking a job with the local telegraph company. To stave off a possible visit from his wife, he penned a cautionary letter to her brother, alluding to threats from the mistress toward his wife if she should attempt to intervene.

But, possibly hedging his bets, Nelson also wrote to his wife in a completely different tone. In that letter, he suggested he might send for her later, and perhaps they could resume their life together in some other town – possibly Placerville.

Back in Carson City, wife Julia was “near dying of grief.” Until, that is, her brother shared with her his letter from Nels, hinting at threats if she tried to follow. It was a completely different story than what Nels had written to Julia. Now, she was angry.

Still suffering from poor health, Julia Savier boarded the stage from Carson to Glenbrook, where she spent the night. The next morning she steamed across Lake Bigler to Tahoe City, then caught the stage to Truckee. There she boarded the train, and stepped off at last in Stockton on July 31, 1871.

Her goal, Julia had told friends, was to gather evidence of Nelson’s unfaithfulness to use in her divorce. Later developments, however, suggested a rather different motive.

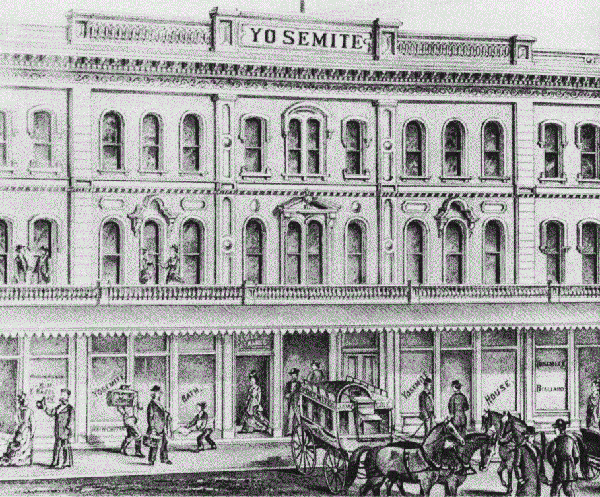

Arriving in Stockton, Julia Savier checked into the Yo-Semite Hotel on Main Street. The lovebirds, she learned, had taken a room on the second floor of the Grand Hotel on Centre Street, about three blocks way. So Julia followed. She requested – and got — a room on the second floor at the Grand, almost directly across the hall from the illicit pair.

That same evening, Julia Savier crossed the hall and knocked on her husband’s door. Nels wasn’t in, but Julia Lake was, and answered the door. She’d been suffering with a “sick headache” (migraine) and had bound up her head.

“Are you sick?” Julia Savier inquired politely, glancing inside the room. On the wall she could see a dressing gown that she’d made herself for Nels for Christmas two years earlier.

“Yes,” the mistress nodded, apparently not recognizing her visitor.

“I’ll make you sicker,” declared Mrs. Savier. With that, she pulled out a Smith & Wesson five-shooter and fired three shots at Julia Lake.

Stay tuned for “Part 2” of the Savier murder saga!