It was a quiet Sunday evening in Genoa. Or at least, it started out that way.

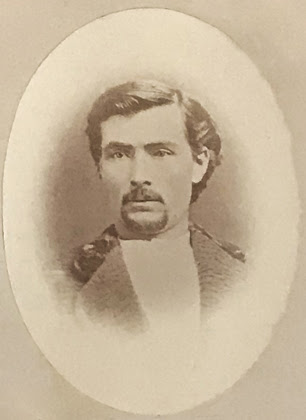

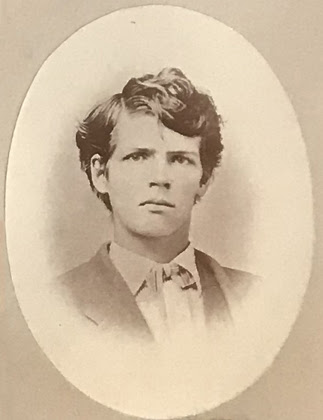

The date was April 16, 1882. The place: Al Livingston’s “first class” saloon on Main Street, Genoa. Jerry Raycraft was enjoying a companionable game of billiards with a friend. A barkeep named Stein was tending bar. And Jerry’s younger brother, Tom, was whiling away the time with a drink – an activity he’d been pursuing a little too long.

Good-hearted and jovial when sober, young Tom Raycraft became obnoxious when drunk. On this particular evening, tipsy Tom decided to insert himself in Jerry’s billiard game. To the barkeep’s dismay, a fight between the two brothers ensued.

This wasn’t the first time that Jerry had had to school his younger brother, and he eventually managed to subdue the rambunctious young man. That matter disposed of, Jerry turned his wrath on Stein, the barkeep who’d kept serving Tom far too many drinks. Jerry vented his displeasure by punching Stein in the belly and walloping his ear.

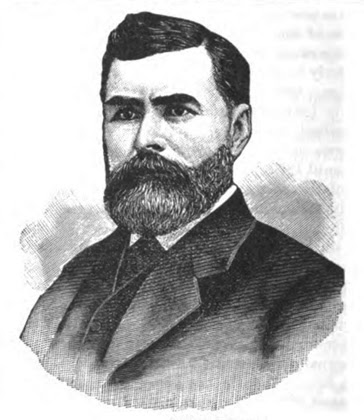

By now the commotion was attracting outside attention. Sheriff James T. Williams was pulled from his supper table to go quiet things down. With a deputy by his side, Williams arrived at the saloon and ordered the combatants to go home.

That was just fine with Jerry. He helped his brother totter the short distance south to Raycraft’s Hotel, and deposited him there. Mission accomplished, Jerry meandered back to the saloon, intending to resume his quiet game of billiards.

But Sheriff Williams halted Jerry Raycraft at Livingston’s front door, threatening to arrest him if Jerry didn’t skeedaddle.

Opinions were exchanged, including something along the lines of: “Who’s going to make me?!” Jerry reached in his pocket. And the Sheriff, thinking Jerry was pulling a gun, grabbed him by the wrist.

But it proved to be a large bowie knife, not a gun, in Jerry’s hand. Wrestling his arm free, Jerry lunged upward, slicing Williams in the hand. And somehow during their struggle, the knife found its way into the Sheriff’s back near his spine.

Badly injured, Williams pulled out his gun. Luckily for Jerry, a guardian angel suddenly appeared.

Jerry’s older brother, Jack Raycraft, just happened to be serving as Williams’ deputy. Stepping between the two combatants, Jack took Jerry safely into custody and escorted him to the jail. “Had the would-be assassin not been promptly locked up by his brother, it is not unlikely that he would have been summarily dealt with,” the Carson Daily Appeal dryly observed.

The knife wound was a serious one, penetrating four inches deep in Williams’ back. For a time, the Sheriff’s prospects looked grim. He eventually rallied, however. And that was more good news for Jerry Raycraft. The Grand Jury indicted him only on a charge of “Assault With Intent to Kill,” not murder.

Jerry’s bond was initially set at $10,000, later reduced to $5,000. Thanks to Henry Van Sickle, E.D. Sweeney of Carson City, and Jerry’s own father, Joseph Raycraft, all of whom stepped up as bondsmen, Jerry was soon sprung from jail.

The Raycrafts, owners of the well-known Raycraft Hotel and Livery Stable in Genoa, were an extremely prominent local family. Finding twelve disinterested jurors to serve at Jerry’s trial turned out to be more than a little problematic. Panel after panel of potential jurors was called and excused. The trial date, originally set for July 31, got continued to August 14, and there were rumors it might have to be moved to Ormsby County to procure a jury. But, after sifting through almost 400 potential jurors and getting down to the last batch of 30 possibilities, a jury of twelve was finally successfully seated.

The trial commenced – and “long and tedious” it was, as the Genoa Weekly Courier grumbled. Surprisingly, District Attorney Moses Tebbs wasn’t sitting in the prosecutor’s chair; perhaps he had a conflict. Instead, lawyers Trenmor Coffin and Gen. Kittrell stepped in as the prosecutors on the case. Former judge D.W. Virgin and Col. A.C. Ellis ably took on Jerry’s defense.

A “very ugly-looking” bowie knife was displayed before the jurors as evidence, and at least ten witnesses took the stand to testify about the stabbing. Jerry’s defense: It had all been an accident! Never mind that Sheriff Williams was wounded in the back.

Following a full day of testimony, closing arguments began at 7 p.m., and continued until everyone finally ran out of steam at 9 that evening. Proceedings ramped up again the next morning, and the jury was packed off to deliberate shortly before noon. Nine hours and ten minutes later the verdict came back: Not guilty. The jury had apparently accepted the defense theory of “accident.” Jerry Raycraft was exonerated. None other than District Attorney Tebbs happily shook his hand.

The Genoa Weekly Courier had a few choice words to deliver about the verdict, however. “The Wheel of Justice Once More Clogged,” snipped its headline on August 18, 1882. The case was yet “another instance of how justice is meted out in Douglas county,” the newspaper’s editor railed. “What’s the good of the law, if this is the way it is to be treated? . . . Was there ever a plainer case of intent to kill?”

A week later, the editor was still hopping mad. Two separate columns elaborated on “some things which we intended to speak of in our last issue” about the “sculdugering.” “The guilt of a prisoner was never more clearly established,” opined the newspaper, hinting that some jurors had volunteered to serve for “political purposes.”

Moses Tebbs, the D.A., came in for his share of venom in the paper for sitting by “like a bump on a log” during trial, then congratulating Raycraft after his acquittal. The newspaper’s tart recommendation: Do away with the District Attorney’s services entirely, “for all the good they are.”

But before you conclude that justice was ill-served in those bad ol’ days, here’s a pinch of salt to leaven the story. George M. Smith, editor of the Genoa Weekly Courier since 1880, resigned the post in July, 1882, the month before Jerry Raycraft’s trial. Taking his place at the editor’s desk was Jesse H. Dungan, son of butcher George W. Dungan. And Jesse was just 18 years old when he penned his flaming remarks.

Jerry Raycraft remained well-liked and the incident seemed to soon be forgotten. He spent much of the rest of his life as a miner, even high-tailing it off to Trinity County with a pair of companions during the Trinity gold rush of 1897. In 1915, Jerry was working a mining claim near Wellington when he fell ill from a combination of nephritis and erysipelas. He passed away a few months later at the age of 62.

Younger brother Tom Raycraft, the one whose intoxication precipitated the whole mess at Livingston’s saloon, managed to get himself into several more alcohol-fueled scrapes, including shooting someone in the leg in 1888 during a “drunken spree” at Gardnerville. Tom suffered an attack of paralysis in 1902 after what may have been a stroke, and passed away in 1903 at just 47 years old. Like his brothers, he was well-known and well-liked in the community. Tom’s obituary lauded him as “generous to a fault,” adding: “Tom Raycraft was his only enemy.”

Like more stories about old Genoa? Check out our latest book (Volume 3)!