Etched in Stone: The Work of W.E. Lindsey

It all started out with just a name: W.E. Lindsey — which kept popping up over and over again in old newspaper stories.

Lindsey, you see, was a marble cutter. And those old newspapers kept talking about Lindsey installing headstones. Beautiful carved headstones. And not just in Genoa, mind you.

Oh, no. He was busily erecting monuments in cemeteries all over Nevada and California: Carson City, Mottsville, Fredericksburg — even as far away as Fort Bidwell, California.

Examples of his work are scattered throughout Genoa Cemetery. It was Lindsey who installed two beautiful tree-like monuments for the Berry family. Lindsey, too, who placed the graceful, curved headstones for Maxwell and Monroe, and a stately pillar for George Rodenbah. And in 1896, it was Lindsey who was awarded a $500 contract for the elaborate “wedding cake” monument for Harriet Walley’s husband, David — just months before Harriet’s own name would be added to the same stone. (That $500 price tag, by the way? Well, in today’s dollars that translates to more than $15,000!)

So, naturally, I got curious. Just who was this Lindsey character? What a fun expedition it’s been to peel back a bit of that mystery!

William Edwin Lindsey was born in Columbus, Ohio on August 18, 1842. His family may have later moved from Ohio to Illinois, as at the age of 21, while the Civil War was raging, William joined the U.S. Infantry on January 1, 1864, as part of the 46th Illinois Volunteers. He mustered-in as a private three days later at Hebron, Mississippi, and mustered-out as a corporal two years later, January 20, 1866, at Baton Rouge.

Lindsey took up the trade of marble-cutting that same year (1866), probably somewhere back in Illinois. He would later be credited with having created “one of the finest soldiers’ monuments in the State of Illinois.” For the rest of his life, Lindsey would be proud of his service to the Union.

By 1870 Lindsey had moved west, living in Visalia, California, and working as a marble-cutter. Ten years later the 1880 Census found him – and wife, Martha — living in Cedarville, Modoc County, in the very northeast corner of California. And, yes, he was still working as a marble-cutter.

And then in late December, 1883, Lindsey began showing up in the Reno news. By now he was described as a “San Francisco marble cutter.” And here’s the news-worthy part: Lindsey was “think[ing] seriously of establishing [a] marble works” in Reno.

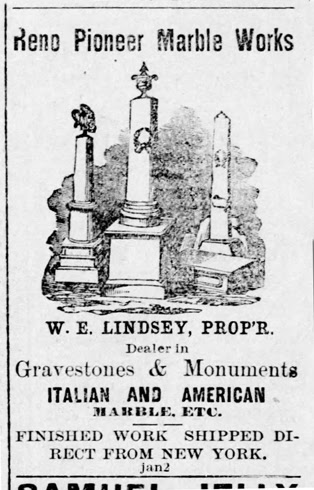

Lindsey did just that, opening the “Reno Pioneer Marble Works” on Virginia Street in July, 1884 right next door to the Odd Fellows building, and began taking orders. That September he moved to a new brick building, owned by C.S. Martin, on the west side of Virginia near Second Street.

By now Lindsey had 18 years of experience under his belt, and was considered “one of the most skilled marble cutters on the coasts.” Lindsey’s 1884 advertisement promised customers: “Nothing but the best Italian marble used.” As for bases, he offered the “best native granite,” sourced from the foot of Kingsbury Grade.

One of Lindsey’s earliest headstone contracts in Nevada was for a Mr. Campbell at Dayton. He also began placing monuments at Genoa Cemetery and elsewhere. Pretty soon he was so busy that in March, 1885, his father moved out from California to help, departing on a “tour through the northern country” a mere two days later to solicit orders for his son’s business. Lindsey also hired a marble-cutter from Chicago to work in his shop, and took off himself for Modoc, Lassen, and Plumas Counties in April, 1885, placing headstones and taking new orders. By early December, 1885, Lindsey was “shipping $1,000 worth of marble to the northern country.” A small fortune, for the day.

You’ll remember that Lindsey was a proud Civil War veteran? Well, in September, 1884, Lindsey was one of the founders of a “Grand Army of the Republic” post in Reno, a veterans’ group for former Union Soldiers. He was quickly appointed the post’s “Commander.”

But by mid-1886, Lindsey had his eye on other opportunities. He sold his main Reno marble business, keeping a small marble shop of his own, and began acquiring stone quarries. In late 1886 he located a thick vein of marble on the old Rickey Ranch in Mono County, five miles from the Bodie Road. This would become his celebrated Antelope Valley quarry, known for beautiful sky-blue marble. The ledge was over 100 feet wide and over 10,000 feet long, and contained marble of at least 14 different colors. Nearby was a separate ledge of onyx said to resemble deposits found in Mexico.

By January, 1887, Lindsey was erecting a sizeable quarrying works at his new Mono quarry, complete with blacksmith shop, stable, boarding house, and multi-saw mill. “This is no doubt the finest marble quarry in the United States,” boasted the Reno newspaper. In February, he shipped some 30 tons of the beautiful blue marble to his shop in Reno, including a huge 4-foot x 4.5 x 16-foot slab weighing 25 tons. He purchased a 32-horsepower engine for his operation in March, and planned to add “ten saws and a polisher.” Workmen carved a “finished specimen” from the beautiful stone to demonstrate its quality. This example was in the shape of a tablet for a child’s grave, with a raised water lily carved below and the words “Our Darling” – no doubt a terrific form of advertising.

Lindsey kept expanding, purchasing new machinery for his quarry and marble-cutting operation in 1888 and again in 1896. And he kept his eye out for additional quarry possibilities. In 1889, he located a 40-acre marble quarry five miles east of Carson City. He also acquired a 65-acre quarry near Mina, Nevada that produced “black Egyptian marble” said to be “jet black, laced with gold and variegated with green and copper-colored veins.” His quarrying equipment must have been massive; one newspaper described a 45-ton block taken from his quarry at Mina to be shipped back east.

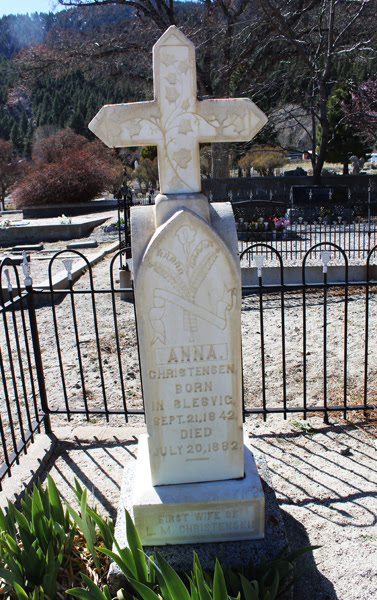

Lindsey evidently did at least some of his monument business on the road. In 1890, he was “working out of the carriage department at R. Gelatt’s barn” in Genoa, finishing several monuments for Genoa Cemetery (which you can still see there today). These included a “pure white marble slab” for the grave of Henry Gray; a “Latin cross cottage monument” with carved ivy for the grave of Anna Christensen; and a slab for the two children of John E. Johns. He was also working on monuments for the Mottsville Cemetery, and one for a cemetery in Lyon County.

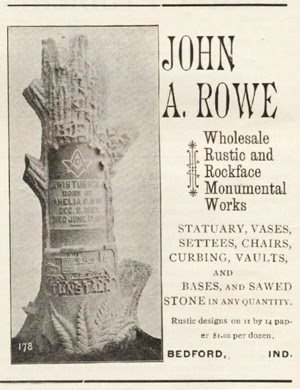

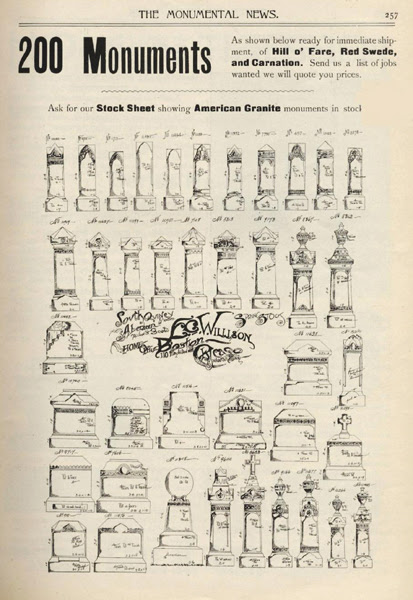

But did Lindsey really carve all those gravestones himself? A few clues suggest he probably didn’t.

Trade magazines for monument makers during that era show that pre-carved stones could be ordered and shipped cross-country via rail. One of Lindsey’s advertisements boasted: “Finished work shipped direct from New York,” suggesting the actual carving had been done back east. And newspapers describing the stones Lindsey was putting up as Italian or Vermont marble similarly suggest they weren’t locally-produced.

Pre-carved stones were apparently a “thing,” according to trade publications of the day. (Who knew, right?!) But Lindsey, of course, may well have added finishing touches, embellishments, and names and dates of the deceased.

By 1893, Lindsey had left Reno behind, and moved his base of operations to Carson City. He’d also located another new quarry: this time a travertine lode near Bridgeport (Inyo County), with hot springs and soda springs on the property.

Lindsey began entering his beautiful quarry products in prominent exhibitions. He won a gold medal for an exhibit of his sky-blue “Walker River” marble at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. And in 1894, he won a gold medal at the San Francisco Midwinter Exposition for a huge block of his travertine – measuring 2 feet thick, 4.3 feet wide, and 7 feet long. Those awards certainly didn’t hurt his advertising; he made sure to tout his gold medal in an 1897 ad!

But as the turn-of-the-century arrived, Lindsey was getting tired. In 1901, he sold his Antelope Valley quarry for the princely sum of $8,000 (nearly a quarter of a million dollars today), and moved with his wife to Fruitvale, California (near Oakland). He still hadn’t lost his passion for prospecting, however; in 1903, he went off on a “diamond-hunting” expedition in Mono County.

In early 1909, Lindsey sold his 65-acre “black Egyptian marble” works near Mina to adjoining quarry owner Davis Brothers of Yerington, with polishing machinery and cranes. It was one of his last acts in life.

William E. Lindsey passed away in Oakland on June 15, 1909, following an operation. He was 66 years old. He was buried in Oakland’s Evergreen Cemetery in the “Garden of Serenity” section. His wife, Martha, passed away two years later, and was buried there beside him.

Unlike the elaborate works of the art he’d left behind for his many clients, Lindsey’s grave marker is modest: a small, simple cube. We don’t know for sure, but with his health was failing and death imminent, he may have carved this last one for himself.

______________

Step back in time to 1894, with these cool photos!

The San Francisco Midwinter International Exposition of 1894 covered 200 acres in newly-dedicated Golden Gate Park. Take a peek at some terrific photos of the event by official photographer Isaiah Taber in this wonderful story by Bob Bragman (San Francisco Chronicle, December 22, 2015).

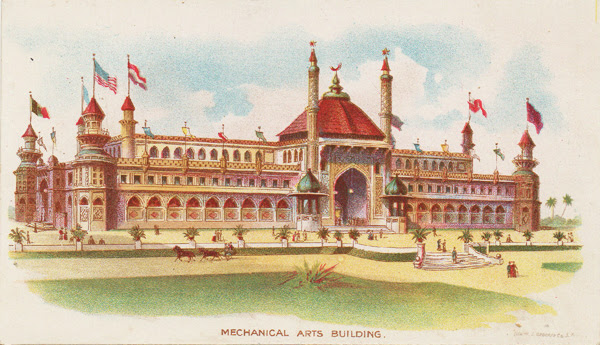

And if you’d like to see the “Official Guide” to the same 1894 Midwinter Expo, here’s a digitized version. Lindsey’s gold-medal-winning exhibit was probably housed in the “Mechanical Arts Building” along with other building stone, ornamental stone, and quarry products, possibly as part of the Mono County Mining exhibit.

_______________________

Check out our most recent book about The Old Genoa Cemetery: Book #3!