Nevada’s Opium Problem, Back In The Day. . .

Blame the Civil War, at least in part, for launching America’s opium addiction. Nearly 10 million tablets of the habit-forming drug were dispensed by Union Army doctors, not to mention various tinctures and powders.

Opium wasn’t used exclusively to treat war wounds, of course. Soldiers facing battle sometimes embraced the “artificial courage” sold by camp followers – much to the chagrin of their commanding officers, who could find users too intoxicated to follow orders very well. Even after the war, veterans with painful war injuries would receive morphine injections from their doctors. It was cheap; it worked; and there weren’t a lot of alternatives.

An epidemic of addiction was the predictable result. In 1875 alone, some 200 tons of opium were legally imported into the United States – only roughly 20% of which was destined for legitimate medical use. And that didn’t count the smugglers’ supply contribution. “Quietly and insidiously, this vice is making its way among all classes, striking down its victims by the thousands,” wailed the New York Sun.

As long as it was only old soldiers, ethnic minorities, and demi-monde denizens getting stoned, polite society turned a blind eye to the opium problem. But it wasn’t long before the demon drug sank its tentacles into the middle- and upper-classes as well.

By the mid-1870s, opium use was already causing considerable consternation in Nevada. Young men and women from Virginia City were paying clandestine visits to Steamboat Springs “to indulge in a quiet pipe of opium,” reported the Alpine Chronicle in September, 1876. Opium-smoking had become “prevalent” among the Carson City and Reno youth as well, as the Carson Valley News lamented that same month. Children as young as 12 were said to be indulging, and Dan DeQuille claimed some proper Virginia City citizens visited the town’s Chinese opium dens “two or three times a week.”

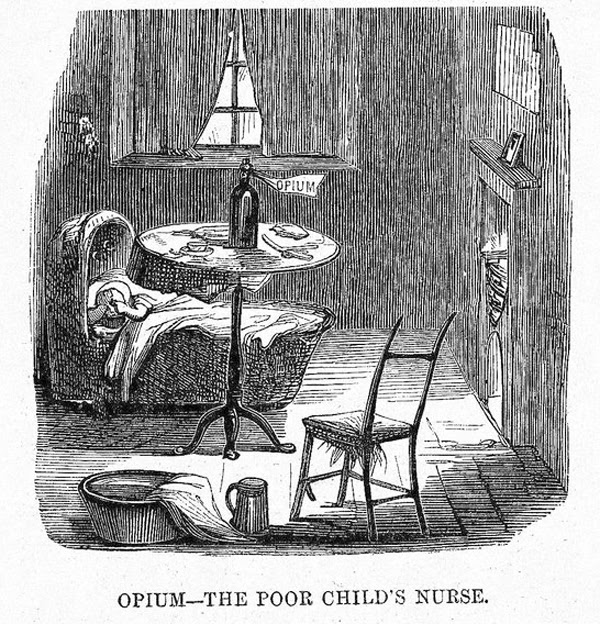

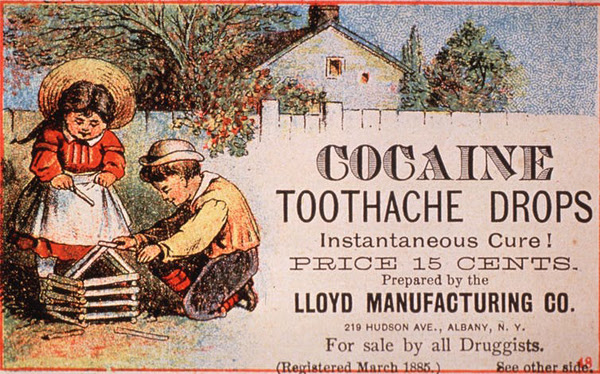

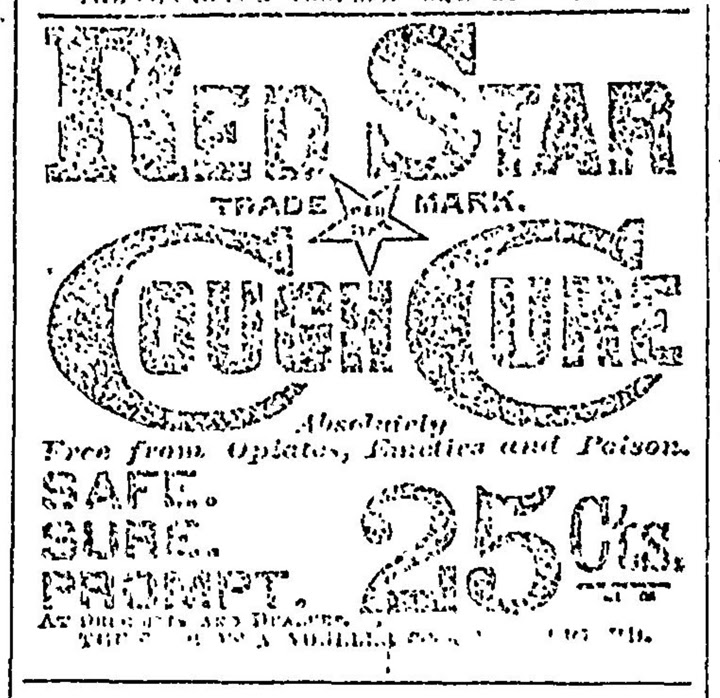

Opium could be acquired in many forms, and in many places. Pharmacies dispensed the drug itself freely on demand – at least until laws eventually began requiring a physician’s prescription. There was laudanum, a mixture of opium and alcohol that became “mother’s little helper” – soothing teething babies and frazzled moms alike. Innumerable opiate-containing patent medicines flooded the market, available by mail-order, from traveling peddlers, or at your neighborhood drugstore – “sure cures” that would surely make you feel better. For a short time, anyway.

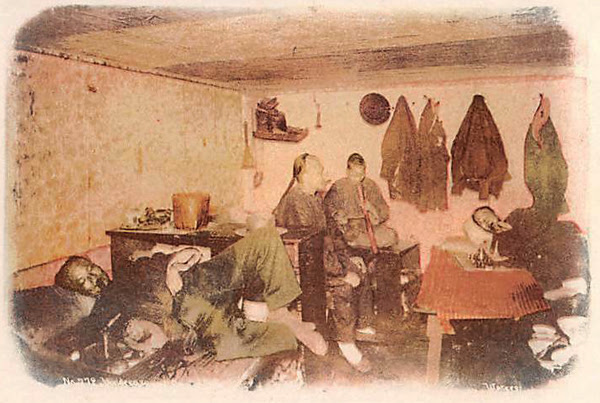

And then, of course, there were the opium dens. Frequently found in the basement or back room of a legitimate Chinese wash house or store, these smoking emporiums sprouted in the Chinatown districts of every Western city. Locations of these dens were often well-known to citizens. Carson City had at least one, located on Nevada Street between 3d and 4th. In Virginia City, a dream-inducing smoke could be found on “H” Street.

The mysterious, back-room nature of opium dens may have contributed to their allure. “Secret signs” or admission tickets written in Chinese were sometimes required for entry. A newspaper reporter for the Yerington Times wrote a lengthy report describing his first experience smoking opium in October, 1876. Entering the basement below Sou Wau’s wash house, he forked over four bits and was initiated into the technique for cooking the “stringy” opium over a lamp. Five pipe-fuls left him feeling “somewhat glorious,” he reported – and, with the “realities of life” obliterated, ready to lie down for a nap.

Most other newspaper editors, however, railed loudly against the moral degradation and “ruin” associated with opium addiction. And slowly, public opinion began to put pressure on politicians to do something about the social hazard of these smoking emporiums.

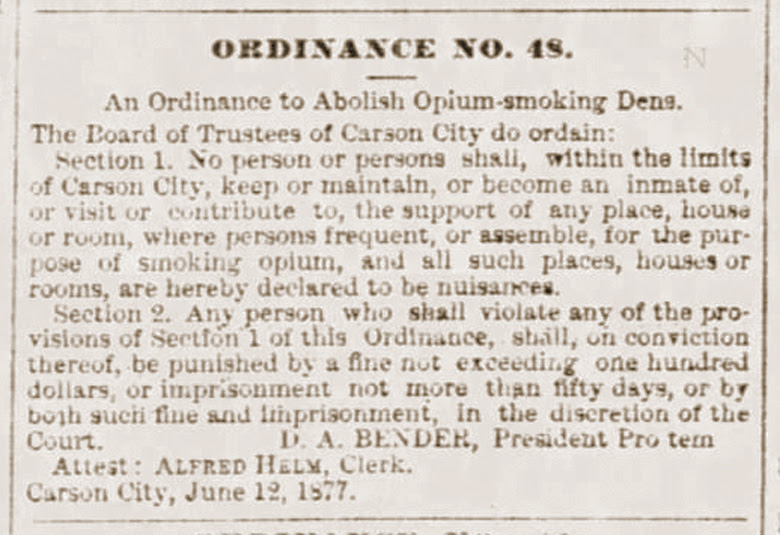

San Francisco, the heart of the opium import trade, finally passed a local ordinance in 1875 making the smoking of opium illegal in opium dens. Virginia City quickly followed, with an ordinance in September, 1876 that banned opium dens within the city limits. Carson City joined the fray in March, 1877, passing “Ordinance No. 48” – threatening up to a $100 fine or 50-day jail sentence for violators.

And in February, 1877, Nevada became the first state in the nation to ban opium dens and the sale of smoking opium, “from and after the last day of March.”

But opium itself remained easily available in medical form, and legal to import. There was money in the nasty stuff – tax money. Duties on legal opium collected at San Francisco were said to have increased by more than $1 million dollars in 1882, thanks simply to anti-smuggling efforts.

Smugglers quite naturally developed creative ways to avoid the hefty duties on opium, such as “losing” a case of opium overboard – into a waiting “fisherman’s” net. Undeclared cargoes were sometimes spirited away in the dead of night on black-painted boats to a quiet wagon waiting on shore, or lifted up through the trap door of a waterfront saloon. Opium was even said to be smuggled in secret compartments in the thick soles of Chinese shoes.

Even after local and state ordinances outlawed opium dens, enforcement in Nevada was spotty. Hired “spies” warned operators of impending raids, and officers might be bribed to look the other way. Opium-smoking by the Chinese themselves was often quietly tolerated, leading “slaves of this fearful vice” in Carson City to disguise themselves in Chinese wigs and clothing to visit the local opium dens. And communities like Gold Hill took the whole “illegal” thing less seriously than larger Virginia City.

Successful prosecution of offenders was sometimes difficult, with witnesses (fellow participants) refusing to testify. But convictions under the “new opium law” were occasionally reported by the local press – especially if the miscreants were Native American or Chinese. One Chinese woman in Genoa was fined $80 by the town’s Justice Court in April, 1881, for example, while her male counterpart got a maximum sentence of $100 or 50 days in jail.

Public tolerance for Chinese businesses used as places for opium-smoking also grew thin. In 1881, a handful of masked members of Reno’s “601” raided dens in the town’s Chinatown, warning operators to refuse admittance to white would-be opium-smokers. A Chinese “wash house” in Genoa known as a “notorious opium den” and purveyor of illegal whiskey was similarly attacked by an irate mob of citizens in 1891, who tossed its stove through a side wall, and largely demolished the front of the wooden building.

Still, the opium den problem persisted. A more formal raid was conducted on the Genoa wash house of Sing Lee in November, 1895, this time by Constable Krummes and his posse. Despite the owner’s protestations that he was “not that kind of a man and didn’t keep that kind of a house,” the evidence collected included opium, pipes, and “all the customary paraphernalia of a first-class opium joint.” Lee was found guilty of keeping a “place of resort” for smoking opium — but fined only $10 plus costs.

Native Americans sometimes patronized the dens as well. A number of Indians at Lake Tahoe were spotted carrying opium-smoking kits in 1896, but explained them away as “headache medicine.” In 1898, Justice Dake of Genoa imposed a ten-day jail term on a Native American convicted of smoking opium. By and large, however, it was the Chinamen who sold the opium who were prosecuted; one Glenbrook distributor paid a $40 fine, for example.

It took a while for the public to figure out the parallel danger from the “medicinal” use of opium. But by the mid-1880s, some new, “pure” remedies proudly touted their lack of “dangerous ingredients.”

Eventually, the federal “Pure Food and Drug Act” of 1906 prohibited sale of “deleterious” drugs and medicines. And the “Smoking Opium Exclusion Act” of 1909 firmly banned possession, use and importation of “smoking opium” in an effort to “stamp out its consumption.

The result – predictably – was a hike in the article’s price. A “can of hop” jumped from $4 to $50.

The opium problem continued, and obtaining a conviction for the illicit drug could still be difficult. As late as 1917, Sheriff Nielsen arrested the Chinese operator of Gardnerville’s “Oriental cafe” for possessing opium discovered in a suitcase. The key to that suitcase was found hidden in the suspect’s shoe. But he was acquitted at trial; “it was impossible to prove that the suitcase belonged to the Chinaman,” after “responsible citizens” came forward to testify on his behalf.

___________