It was over 50 years ago when I first spotted this ancient, lonely headstone beside the river in New London, Connecticut.

The cemetery itself was knee-high in weeds. Modern steel train tracks ran right beside this ancient holy ground. Hoboes who’d hopped off their ride huddled by their warming fires nearby. But even as a child, my imagination was piqued by this forgotten headstone.

Who was “William Peck,” who’d died in 1798 aboard the Good Ship Sally”? And what had killed him? He’d obviously died way too young, at just 21; it said so, right on his stone. His home was nearby Norwich, CT. That, too, had been thoughtfully included in the inscription.

We can only guess that young William Peck was a sailor aboard the Good Ship Sally. But was she a whaling ship, a merchant brig, or (heaven forbid) a slave ship? Where did William sail? And what killed him aboard that ship at the tender age 21?

William Peck’s marker was one of just two or three formal, carved headstones that remained in the graveyard. But there were many other large, black rocks scattered about. And those seemed to mean – well, something. Were they additional burials? It sure looked that way.

According to local rumor, this once had been an Indian burying ground long before white men arrived. Or perhaps that was our childhood imagining. But it sure looked like dozens of people had been buried here. A long, long time ago.

I’ve never forgotten William Peck and his proud, lonely grave. And thanks to the magic of the internet, I was able to learn more about the spot where he’s buried.

Turns out this early graveyard has a name: It’s the Rogers Cemetery, named for John Rogers, Sr., who died in in 1721 and was probably the first settler interred here. The cemetery may originally have spread out over an acre and a half, and included as many as 60 or 80 burials. But the Rogers family disapproved of formal monuments for the dead – which doesn’t help later historians, of course, but likely explains the scattering of rough stones.

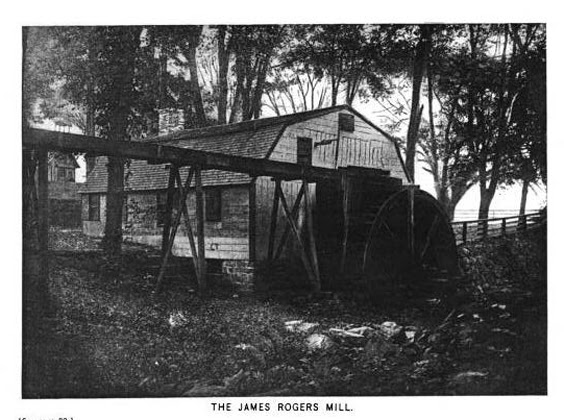

John Rogers, Sr. was born in 1648 into a prominent local family. His father, James, operated the New London flour mill (now known as the Winthrop Mill), and by the mid-1660s father James had become the wealthiest man in town.

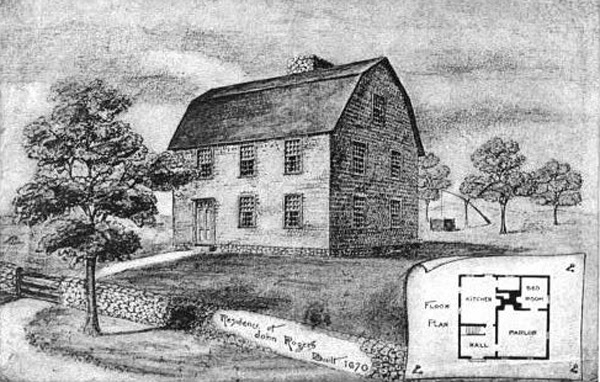

Son John (Sr.), too, did well for himself. He became the owner of Mamacock Farm two miles from New London, spanning both sides of the Norwich Road.

An intelligent but independent-minded young man, John Sr. became disillusioned with both the local Congregationalists and the Seventh Day Baptists. About 1677, he founded his own religious sect, launching what became known as the “Rogerenes.” The group’s main mission seemed to be flouting religious norms of the day and irritating the staid Congregationalists who ran the town.

Tenets of the Rogerene faith included evening (not daytime) communion, and water baptisms. They recognized Sunday as the Sabbath, but unlike the Congregationalists, accepted no prohibition on working on that day. Like the Quakers, they believed in silent worship – although singing was allowed. Also like the Quakers, they favored equal rights for women, and stood staunchly against both war and slavery.

But perhaps most upsetting for their religious opponents, Rogerenes refused to pay taxes to support the local Congregational Church and its salaried minister – the only denomination recognized at the time by the Connecticut government.

The group delighted in tormenting their opponents – especially Gurdon Saltonstall, the prim-and-proper Congregational minister who later became governor. In one oft-repeated story, a Rogerene man and woman once interrupted Saltonstall’s dinner, scandalously declaring their marriage had been solemnized only in the Rogerene faith and rudely inquiring what Saltonstall intended to do about it. The canny Saltonstall glanced up from his dinner and calmly pronounced the pair husband and wife.

But the sect’s provocations continued. Rogerene adherents would march through the streets of New London on Sundays, announcing their intention to go to work. More disruptive yet, they attended services wearing hats as a form of protest, or stood up to argue points of theology with the pastor. In 1695, Rogers (Sr.)* reportedly rolled a wheelbarrow inside the church, disrupting the service and demonstrating his intention to work on the Sabbath.

Surprisingly, the religious renegades won at least a few sympathizers in town. But in the eyes of the law, they became nuisances. Neither fines nor imprisonment seemed to deter them. Rogers (Sr.) was once sentenced to stand on a gallows for 15 minutes with a noose around his neck. One or two Rogerenes were tarred and feathered.

That only escalated things, of course. In 1695, Rogers, his son, his sister, and a servant were convicted of burning down the New London meeting house, an offense for which Rogers (Sr.) spent four years in prison. The experience failed to reform him, however. Rogers was later imprisoned again for a further series of offenses, including “entertaining” Quakers in his home.

In 1708, Saltonstall (now Governor) tried to step up the pressure by having Rogers (Sr.) declared insane and incarcerating him. But protests by his sect continued. In 1721, irate at being taxed for New London’s Meeting House (church), a group of Rogerenes took over the building, temporarily preventing the minister from holding services.

As part of his belief in faith healing, Rogers (Sr.) traveled to Boston to tend the sick in 1721. Soon after his return, he came down with smallpox. He died in October, 1721, and was buried here beside by the river. Two other family members (Bathsheba Rogers and John Rogers III) died just a few months later, and were buried here as well. In 1751, Rogers’ son, John Jr., formally set aside this spot for family burials, just two years before he died of apoplexy, in 1753. John (Jr.) was interred here as well, mourned by something like 15 of his 18 children (most of them also considered “sturdy Rogerenes”).

The Rogerene faith continued to flourish for another century. Although not truly Quakers in the George Fox tradition, Rogerenes were also pacifists and were sometimes mislabeled Quakers due to their similar beliefs and silent services. So it was Rogerene residents (and not true Quakers) who prompted the naming of Waterford’s Quaker Hill and Ledyard’s Quakertown.

In 1815, some of the Rogers cemetery was eroded by the Great September Gale. The property was transferred in 1822, although members of the Rogers family continued to be buried there at least as late as 1860. Meanwhile, the New London, Willimantic & Palmer Railroad unceremoniously ran a rail line right through the old graveyard in 1849.

Around 1906, Rogers descendants restored the old cemetery as best they could and fenced the perimeter. The land was acquired in 1911 by adjacent Connecticut College. Despite the ravages of time and weather, a ground-penetrating radar survey in 2009 identified 40 possible remaining graves. A plaque marking the “Rogers Family Burying Ground” was finally added to a large boulder to commemorate the site in September, 2019.

As for the mysterious William Peck — well, in 1958, some 160 years after his death, the newspaper reported the horrifying news that someone had tried to dig him up! Luckily, they didn’t succeed. But sadly, Peck’s story remains a mystery. What caused him to be buried here in 1798? Was he a Rogerene, or did his shipmates merely find it a convenient spot to inter a body? Or could this be simply a memorial stone (new word for me: a cenotaph!), with his body buried elsewhere, perhaps buried at sea?

Unfortunately, his all-too-common name makes tracing him difficult. A different William Peck died at Berbice (Guyana) in 1798. But that William seems to be buried at Cranston, Rhode Island, with his parents Elihu and Rebecca. There’s yet another William Peck who shows up on another branch of the Peck family tree, a son of Enoch and Mary Peck. But that group of Pecks hailed from Fairfield (Newtown), Connecticut — hard to reconcile with “our” William of Norwich.

Norwich, on the other hand, had its own prominent Peck family. Joseph Peck operated a well-known inn there from 1754 until his death in 1776. Amazingly, that old inn (now 8 Elm Avenue) is still standing.

So could William be related to Joseph Peck of Norwich? Well, it’s possible; after all, his grave lies just a dozen miles away from that town. But so far, at least, we haven’t turned up any link between innkeeper Joseph Peck and our mysterious William.

And yet another mystery: William Peck seems to be the only person buried in the Rogers Cemetery whose surname wasn’t Rogers. So how did that come about? Was he married to a Rogers?

Here’s hoping the magic of the internet will eventually work its magic again – and allow us to learn more about young William Peck, his life (and death) aboard the Good Ship Sally, and how he wound up with this beautiful, lonely headstone in the old Rogers Cemetery.

_______________

* Later accounts of the Rogerenes sometimes understandably confuse John Rogers Sr. (born in 1648, died 1721) with his son, John Rogers Jr. (sometimes called “Second”)(born 1674, died 1753). It was John Sr. who was the founder of the Rogerenes, converting not only most of his children (including John Jr.) but also his father, James Rogers (born ~1615, died 1687). Most of the often-cited incidents attributed to “John Rogers” appear to be acts by John Sr., though his son, John Jr., was also a Rogerene and was apparently involved in burning the meeting house. For a wonderful genealogical history of the Rogers family with a good discussion of the Rogerenes, see James Rogers of New London, Ct. & His Descendants (Boston, The Compiler, 1902) (Google Books): https://tinyurl.com/6xwz5jax.

For more of the history of New London, check out our other New London history posts here!