The Victorian Parrot Craze

Victorians adored their feathered friends. Gold Hill in 1876 was said to boast “more parrots than any city or town on the Pacific Coast.” The Nevada State Journal quipped: “You may walk for miles and miles and never hear anything said but ‘Pretty Polly!’ and ‘Polly wants a cracker.’”

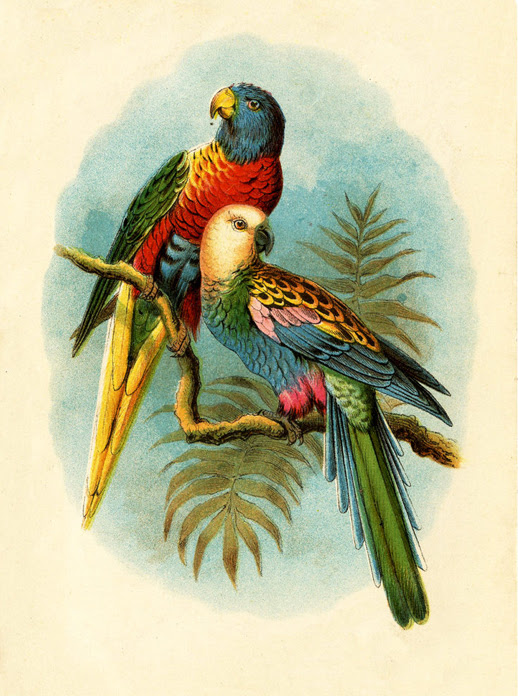

Highly intelligent and valued for their talking abilities, parrots made beautiful and exotic pets. So perhaps it was little wonder that by the 1870s and 1880s, the Comstock had become something of a parrot paradise.

Retailers could turn a pretty profit on avian inventory, too. Customs value for a parrot in 1870 (the taxable value for import duties) was $4; cockatoos were even less, at just $3. But at retail, sellers often commanded considerably more for birds, largely depending on a bird’s speaking ability. As the tongue-in-cheek Carson Daily Appeal put it, “a good parrot, one that swears in two languages, is worth about ten dollars or higher, according to expertness in profanity.”

Sellers quickly realized the importance of teaching the birds a few key phrases. Noted the Pioche Record in 1884, “small talking parrots are the favorite pet birds of young ladies this season,” with dealers coaching their birds to repeat endearing phrases like “Kiss me, darling.”

The craze for parrots was nothing new, of course. Parrots had long been the companions of royalty. Henry VIII owned an African Grey parrot. Queen Victoria, too, kept a Grey named Coco, who’d been taught to sing “God Save The Queen.”

The Comstock’s own “royalty” owned parrots, too. In 1889, Mrs. Mackay (aka “the Bonanza Queen”) kept a “wonderful green parrot” at her home in London’s Sandringham neighborhood. Positioned in an open window, the parrot “attracted hundreds of people every day to hear it talk” — and gave surprisingly accurate answers to questions thrown its way.

Once asked what day it was, for example, Mrs. Mackay’s parrot not only identified the correct day of the week (Sunday), but admonished listeners to “Go to prayers,” adding the admonishment “Ora pro nobis” (pray for us). After which performance, as the Genoa Weekly Courier reported, the bird “fell into a paroxysm of laughter.”

News accounts of parrot antics from around the country were eagerly recycled by local Nevada newspapers. Stories ranged from the humorous to the astonishing – helping sell not just newspapers, but probably more feathered companions as well.

One funny story recounted by the Reno Gazette-Journal in 1884 involved a Cincinnati fire captain left chasing after his fire rig when a voice from inside the firehouse bellowed “All right, go ahead!” to the driver. Off ran the horse-drawn engine, leaving the surprised captain behind. Yup, the voice belonged to a mischievous parrot, who seemed to “thoroughly enjoy the commotion he had aroused.” A later story, also from Cincinnati, described a parrot foiling a robbery by biting the burglar so badly he left bloody fingerprints behind on the window sill in his hasty departure.

Stories about local birds made the pages of Nevada newspapers, as well. In 1883, a Genoa family kept a pet magpie, who was known to help himself to the contents of the sugar bowl and hide household objects as large as a pair of scissors. A parrot in Carson City once serenaded its household with a stirring rendition of The Watch on the Rhine (a patriotic German song) after “tak[ing] a bath in a pitcher of beer from Klein’s brewery, which had been left on the table,” according to an 1880 story. And in Hawthorne, Nevada, a large, green parrot who’d been lovingly tutored by Native American ladies was said to speak Paiute so fluently that visiting tribal members were “thunderstruck” and suspected the bird of being possessed.

In 1878, Thomas McCommas, owner of Genoa’s Central Hotel, purchased a young parrot and spent many hours lovingly teaching “Polly” to talk. He’d soon come to find out, however, that the bird picked up bad words all too easily. After a single night listening to a drunken guest carry on, Polly’s vocabulary had enlarged to include a long litany of profanity.

“Learning bad words” was apparently a frequent problem for parrot owners. Feathered friends should be kept well away from town, cautioned the Pioche Record in 1873, “if it is desired to educate them as Christians.” The solemn occasion of the funeral of President Andrew Jackson in 1845 was interrupted by his African Grey, swearing so badly that the bird had to be removed from the ceremony.

Though parrots were loved by their owners, proper parrot care was probably not terribly well-understood. Thomas McCommas’s parrot Polly, for example, lived just a few years. Her passing was sadly noted in the local press in 1881. She was a “good bird,” the Genoa Weekly Courier commented, though with a “remarkably shrill voice.”

But unlike Polly, some parrots in early Nevada did manage to live long and happy lives. Genoa brewer A. Schwarz kept a parrot who, at least in his “youthful days,” could rattle off phrases in English, German and Spanish. By 1882, this beloved parrot had been a fixture in the Schwarz family for 27 years, and was reportedly nearing 70 years old.

___________________________