Tarantula Juice & Other Tales from Empire, NV

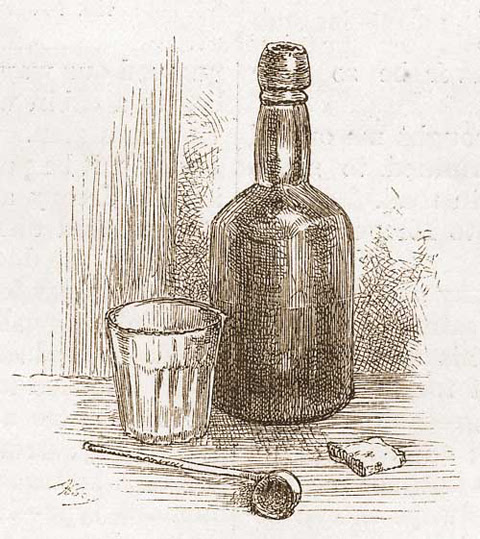

Dutch Nick’s saloon in early Empire, Nevada was infamous for its ‘tarantula juice’ – a homemade concoction of wood alcohol laced with strychnine, tobacco juice, prussic acid, and other foul ingredients. Some say the name derived from the drink’s after-effects, said to resemble the sensation of bugs crawling over your skin. Others noted that drinking whiskey until you were intoxicated was an accepted remedy for a real-life tarantula bite. Or perhaps it was simply the ‘bite’ of that first awful swallow that gave the drink its name.

Dutch Nick’s version of the drink was famous as one of the worst – or the best, depending on one’s perspective. Dutch Nick’s own obituary recalled that travelers on Pioneer stage from Sacramento to Virginia City often stopped to pay two bits at Nick’s tavern for “a drink of liquid that in five minutes after imbibing, would turn a man into a fiend, or else make him think he had the Comstock Lode in his vest-pocket.” (For more about Dutch Nick Ambrose himself, see Part 1 of this story!)

The strychnine, in particular, wreaked havoc on tarantula juice imbibers. Its effects were said to resemble those of modern-day methamphetamine, prompting users to become irritable, impulsive, and combative. Couple that with the alcohol, and it’s not too surprising that patrons of Dutch Nick’s saloon not infrequently made the news, though it wasn’t always the tarantula juice that landed them in trouble.

In October 1861, for example, newly-wed James (or Juan) Gonzalez died shortly after imbibing several drinks at Dutch Nick’s. And in this case, foul play was suspected.

A saloon-keeper himself at Gold Hill, Gonzalez had recently gotten married in Carson City, after which the happy couple had ventured east to Empire to attend a ball at Dutch Nick’s. The morning after the ball, Gonzalez returned to Dutch Nick’s establishment and tipped back a few with Nick’s barkeep, a man named Oswald. A few hours later, Gonzalez’s wife discovered her new husband back in their hotel room, “his face black and contracted.” He died shortly thereafter.

It seemed clear that Gonzalez had been poisoned by those drinks at Dutch Nick’s saloon. But surprisingly, rather than blaming the tarantula juice itself, suspicion quickly turned on the bartender. Oswald, it seems, had “on various occasions expressed great admiration for Gonzalez’s wife.” And that, it was thought, had been motive enough for him to poison the drinks.

Dutch Nick himself was mentioned in an 1870 column in the Carson Daily Appeal in connection with a horse-racing scam. A racer named Faylor had set the con in motion by sending $100 to his mark, a faro dealer in Empire whose name, ironically enough, was Bright. “Place a bet on me to win the race,” Faylor had instructed the not-so-bright Bright. Wink, wink, nod, nod.

Confident that the horse race had been rigged and the bet was a ‘sure thing,’ Bright eagerly wagered Faylor’s $100 bucks and threw in another $900 of his own. Dutch Nick, it’s said, happily took up that bet. And exactly as planned, Faylor promptly lost the horse race — leaving Dutch Nick and Faylor to split the ill-gotten $900 bucks.

In 1873, a quarrel that began at Dutch Nick’s saloon mushroomed into a shooting affair at a bar down the street. The night began with “Butcher Jack” Kyle and a teamster named Jones, who fell to arguing in Dutch Nick’s saloon. The pair continued their dispute later on that evening inside Shoemaker’s saloon, where they “fell to wrangling again.”

In the heat of the argument, Butcher Jack hit a third man named Schneider in the face with a heavy whiskey tumbler. Bruised and angry, Schneider pulled out a six-shooter. But whether from nerves or whiskey, his first bullet struck his own left forefinger before continuing on to strike another bystander in the thigh. Schneider squeezed off a second shot, this one successfully winging Butcher Jack in the shoulder.

According to the newspaper account, the unlucky bystander who’d been wounded calmly “resumed the poker game over which he was engaged when the shot struck him, remarking that he was going on to win money enough to pay the doctor bill which he would have to incur on account of the wound.” And there, at least, he proved lucky, winning $40. A doctor was called, who also managed to extract the bullet from Butcher Jack. And Schneider, the victim, proved lucky as well; given the melee, his action with the gun was deemed self-defense.

A different shooting occurred in 1876, this one on the sidewalk right outside Dutch Nick’s saloon. A man named Sloan who worked there as a faro dealer was shot to death as he exited the saloon by John Murphy, proprietor of the nearby Nevada House and a former guard at the Nevada State Prison.

Murphy and Sloan, it seems, had been “on bad terms” for some time. Murphy contended that Sloan tried to fire on him first, and he’d only shot back in self-defense. The dead man, of course, was in no condition to give his own version of events. Other reports, however, suggested that the victim was unarmed when he was attacked by Murphy, but had “heeled himself” (procured a gun) during the melee.

Another shooting occurred in 1879, although this time, heavy drinking saved the day by impairing both parties’ aim. Joseph Lopez began the evening by getting “very drunk” at Lebo’s saloon, pawning his silver watch for more liquor when he ran out of money. An hour or two later, Lopez had forgotten about the whole transaction, and began accusing a friend of stealing his watch.

Eager to avoid trouble, the friend left Lebo’s and settled himself outside Dutch Nick’s with a group of other men. Lopez staggered by, briefly entered Dutch Nick’s, then exited and “without warning, drew a revolver and fired three shots” at his former friend, none hitting the intended target. Now angry, the victim pulled his own gun and fired off two shots in retaliation. Perhaps he, too, was drunk or simply bluffing; those bullets, too, did no harm. Lopez was arrested for attempted murder. He proved to be “so greatly prostrated from the large quantity of bad whisky he drank” that his trial had to be postponed two more days so he could “sober up.”

An attorney in 1879 cited Dutch Nick’s bad whiskey as he asked the judge for leniency for his client, a convicted horse thief. The thief, his lawyer argued, had been “boiling drunk when he took the horse from Weder’s stable” after consuming three glasses of ‘rat poison’ at Empire. The judge wasn’t swayed, however, sentencing the thief to six months in jail plus a $40 fine. Quipped the Reno Gazette-Journal: “the court had evidently never sampled the ‘rat poison’ at Dutch Nick’s.”

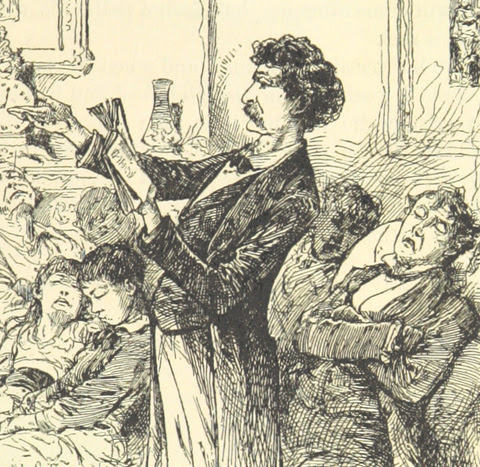

One crime that didn’t happen at Dutch Nick’s was the celebrated ‘Hopkins murder’ concocted by Mark Twain in 1863, while a reporter for the Territorial Enterprise.

Twain’s fertile imagination spun a fictitious story about a sensational murder at Empire near Dutch Nick’s, involving a man pushed to the brink after selling his valuable silver stock to buy worthless, inflated California stocks. The dejected investor supposedly killed his entire family, then cut his own throat and rode all the way to Carson before falling dead.

Many readers, however, failed to appreciate the fictional nature of this tale, and were shocked and horrified by details of the “bloody massacre.” They were even more offended once they realized they’d been duped.

Twain had intended the story as a satire to embarrass San Francisco papers which had, indeed, pumped worthless California stocks. He’d inserted enough bogus details, Twain thought, that readers certainly would know the tale wasn’t true. Hopkins, the purported killer, for instance, was a bachelor, so he couldn’t possibly have murdered a nonexistent wife and children. Twain had also embellished the area near Dutch Nick’s sagebrush headquarters with nonexistent details like a “dressed-stone mansion” and a “great pine forest.”

“The idea that anybody could ever take my massacre for a genuine occurrence never once suggested itself to me,” Twain would later write. “But I found out then, and never have forgotten since, that we never read the dull explanatory surroundings of marvelously exciting things when we have no occasion to suppose that some irresponsible scribbler is trying to defraud us. We skip all that, and hasten to revel in the blood-curdling particulars and be happy.”

Despite having provoked the ire of his reading public, Twain remained unrepentant. In October, 1866, none other than Twain himself was scheduled to deliver a lecture at Dutch Nick’s establishment. The topic he had chosen: “The Massacre of the Hopkins Family.”

Dutch Nick’s patrons must have loved it.

________