Pioneer Justice Was Swift:

When Snowshoe Thompson skied into Placerville on February 2, 1856, it wasn’t just the Carson Valley mail he brought with him over the mountains. He also carried the latest gossip.

Among other news Thompson brought to eager listeners was a report of a crime — some $75 had been stolen from Mark Stebbins, proprietor of the station at Eagle Ranch (today’s Carson City). Two men had been arrested for the theft, and an informal ‘people’s court’ had been convened. But to the chagrin of Stebbins, both suspects were released for lack of evidence.

Two weeks later, Snowshoe had an update to share: one of the two suspected thieves had been re-arrested. Charlie Kensler, it seems, hadn’t learned his lesson. He was suspected of stealing another $12 in gold dust from Stebbins, the original victim.

This time, instead of the ‘people’s court,’ Kensler was hauled before Judge Orson Hyde, the newly-appointed Probate Judge for newly-created Carson County. An imposing figure with an equally imposing temper, Hyde had arrived at Mormon Station in June, 1855, charged with setting up the county government. It was a huge undertaking and Carson County itself was also huge, encompassing all of today’s Douglas, Washoe, Ormsby, Storey, and Lyon counties, along with sections of Esmeralda, Churchill, and Humboldt counties thrown in, too.

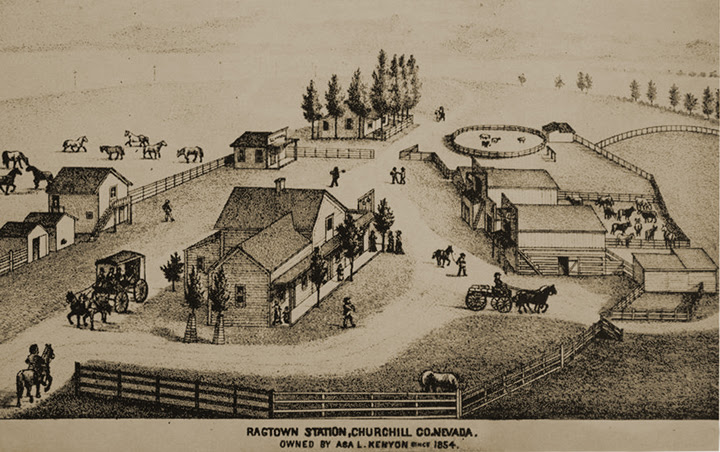

Justice for the accused would be speedy indeed. Just one day after Charlie Kensler’s arrest, his trial convened in Genoa at the home of early settler Asa Kenyon. Although Kenyon happened to be spending the winter at Genoa that year, he was perhaps better known as the proprietor of a log cabin “station” at Ragtown, at the western edge of the Forty Mile Desert.

Three nearby settlers were hastily summoned to serve as a jury: G.W. Taylor, Warren Smith, and R.D. Sides (who later would become the target of Orson Hyde’s infamous curse). Dr. Charles Daggett, a medical doctor who also conveniently held a law degree, had already been dubbed the new county’s Prosecuting Attorney.

Seven witnesses were called to testify about the theft, two of them speaking on behalf of the accused. Kensler also shared with the jury his own version of events, which may have been a bit long-winded; court records reflected that he was “patiently and fully heard.”

The three jurors took just ten minutes to arrive at their verdict. They not only found Kensler guilty of petit larceny, they also decided his punishment: six months at hard labor “with ball and chain.” Kensler was to be hired out “to the best advantage for the county” at $12 per month.

Asa Kenyon, a blacksmith, fabricated the necessary ball-and-chain and submitted a whopping $25.75 bill for his services, though the court knocked that down to $15 – still a hefty charge. Other expenses for the case included “keeping the prisoner” for two days ($10); Daggett’s fee as prosecutor ($15); witness fees for seven witnesses ($7); constable’s fees, which including bed, board and clothing for the prisoner ($51); and Judge Hyde’s own fee including clerk costs ($15). All told, the cost of prosecuting Kensler came to $116 for a $12 theft. As historian Bob Ellison aptly put it, the case was “the new county’s first taste of the expense of justice.”

Kensler served out at least part of his six-month “hard labor” sentence. But baling hay, digging ditches, or fixing roads would have been tough to perform while attached to a ball and chain. And at some point, the shackling — and supervision — may have wavered. By 1880 nobody seemed to remember the erstwhile thief. Thompson & West’s History of Nevada concluded “it is safe to presume that he . . . escaped.”

So, what did become of Kensler? According to the Grass Valley Morning Union, a similar-sounding ‘Charles Kensler’ died on January 22, 1915 in the hospital at Nevada City, California. A native of Michigan, Kensler was 78 years old and had been living in Spenceville, California before his death.

We can’t be certain that it’s the same Charlie Kensler, of course. But this California gentleman would have been an impressionable 19 years old when the gold dust was pinched. And it would hardly be surprising if putting a mountain range between himself and Judge Orson Hyde had felt like a grand idea.

_________________

Many thanks to historian Bob Ellison, who shared this fascinating story (and so many more!) in his impeccably-researched “Territorial Lawmen of Nevada” (Vol. 1) (Hot Springs Mountain Press, 1999). Any added errors are strictly my own.