Ever heard of “bastardy bonds”?

I certainly hadn’t. Not until I was researching my own family history, when TMCC genealogy librarian Sue Malek helped me discover a whole book about North Carolina Bastardy Bonds (with, yes, a few family surnames inside!)

Turns out bastardy bonds were an early way of mandating child support, ensuring that “base-born” children would not become a burden on the county (or the local poor house).

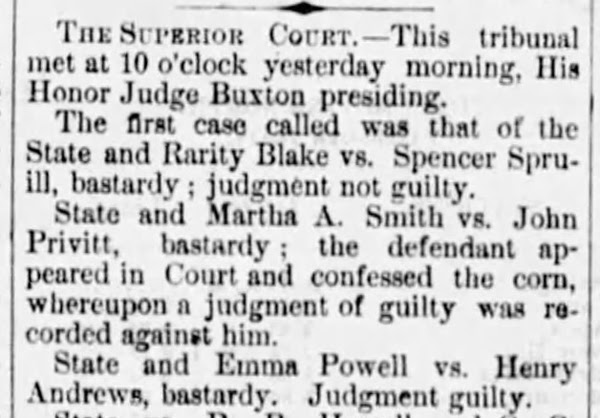

Due process was apparently scant in those proceedings. Pregnant, unmarried women would be hauled before a judge and required to spill the name of the father. She (or other family members) could post the bond if they preferred to keep the whole matter private. But refuse to name the father and refuse to post a bond? The judge could send the recalcitrant mother to jail until she rethought her decision.

Once the purported dad was named, he got his own day in court. Occasionally paternity would be contested and the case would go to trial. But more often, fathers simply admitted paternity, paid a fine, and posted the required bastardy bond to guarantee support of their offspring. If the father later defaulted, that’s where the bond came in handy: the court ordered the bondsmen to pay up.

Child support for dads was minimal – between $16 and $30 a year. And that continued only until the child turned seven years old when, under NC law, all “base-born” children had to be apprenticed out to learn a useful trade.

Bastardy bonds came into use in North Carolina as early as 1736, during British colonial days. And it wasn’t only North Carolina that embraced the bastardy bond practice. Ohio, Maryland and Tennessee also adopted them. In some places, these bonds continued to be employed in paternity cases as late as the 1890s.

Illegitimate births would have been a relatively rare occurrence, you’d think, given the austere morals of the day. But in fact they were hardly unusual. Of the 35,000 births in New York City in 1871, for example, 2,500 were out-of-wedlock babies.

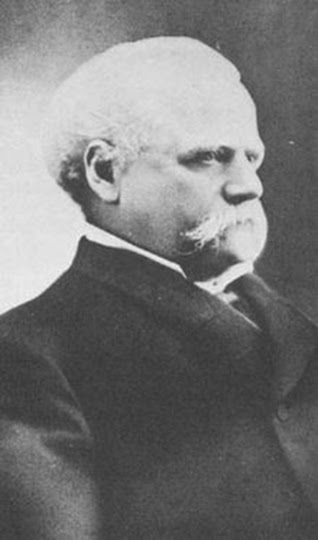

Alpine County’s mining magnate Lewis Chalmers fathered his very first child out-of-wedlock back in Scotland. In April 1850, Chalmers was forced to acknowledge a baby with Elizabeth Moir of nearby Banff. Turns out the church played a role in confirming paternity in that case; the baby’s birth registration noted that the “Kirk Session” of the Banff Kirk (Church) had investigated the circumstances of the birth and was satisfied that Lewis Chalmers was the father. Baby Lewisa (Louisa) officially received the Chalmers surname.

Luckily for the little girl, her grandparents stepped in and raised her. Other out-of-wedlock children might be informally adopted or simply “passed off” as a relative’s child. But as time went on, placement services arose, and morphed into a scandalous baby-selling business. Elko’s Weekly Independent reported in March 1892 that 500 “unfortunate waifs” each year were being shipping around the country by one New York foundling asylum. For would-be parents, the adoption process was simple and businesslike: just “go to the pen, pick out the baby that takes your fancy, pay the stipulated price, and it’s yours.” The child’s parentage was “carefully concealed” by the sellers to avoid any inconvenient “future entanglements.”

Scandals involving illegitimate children cropped up on occasion here in Carson Valley and nearby communities, too. Col. Frank Rickey of Markleeville was once rumored to have fathered a child with his wife’s daughter, for example. And in 1897, Emma L. Robeson of Virginia City sued Louis V. Averill of Lake Tahoe for “abandoning” his illegitimate daughter, conceived while Emma was employed by Averill’s parents in Lake Valley. The outcome of that support case is unclear, but three years later the purported father was in San Francisco, operating a cigar store.

Sadly, not all unexpected babies survived — nor did their mothers. The body of one newborn baby boy was found at the upper end of Genoa in 1884 with a cord around its throat. A two-day-old infant’s body was discovered concealed on the Divide in 1906. Young Johanna Lammkiller died in Gardnerville in 1895 as the result of a self-induced abortion. And in Bodie, another young lady died in 1880 after an abortion thought to have been performed by a “well known physician” in town. In one especially horrifying story, the proprietress of a Milwaukee “lying-in house” for pregnant women was accused in 1886 of charging her clients $300 to put babies “out of the way” via a darning needle through the heart.

But for some illegitimate children, at least, there were happy endings. Lewis Chalmers’ out-of-wedlock daughter, Lewisa, grew up in her grandparents’ home in Scotland, married a traveling sales representative, and had eight children of her own – and a good life in Canada.

And a very happy ending indeed ensued in one of the most prominent Victorian legal cases involving an illegitimate child. When self-made millionaire Thomas Henry Blythe died in 1883 without a will, a horde of claimants quickly descended – nearly two hundred of them, making various claims. Litigation followed for the next quarter century. But in the end, it was Blythe’s illegitimate daughter, Florence, who prevailed — and inherited Blythe’s four-million-dollar estate.

______________

* Like to research your own family genealogy? Visit TMCC’s amazing Genealogy Library. You can also tune in for genealogy librarian Sue Malek’s free weekly Zoom classes. https://libguides.tmcc.edu/c.