Today, it’s hard to imagine a gun battle taking place in the middle of Genoa. But that’s exactly what happened back in 1860, in a raucous dispute over property. And amazingly enough, there’s a silent reminder of that altercation you can still see today.

Young Warren Wasson was minding his own business on February 11, 1860, hauling a wagonload of milled lumber to his property on the south side of Genoa Lane, with an eye toward building himself a small house.

But town luminary John Trumbo was upset — and not only about Wasson’s house-building idea; he was irate at Wasson’s claim to the land. Trumbo, you see, was a son-in-law of Col. Reese, who’d originally claimed the entire area back in 1852. And Trumbo had previously warned Wasson not to set foot on the disputed property – a warning Wasson had blithely ignored.

Seething as he watched Wasson drop his load of lumber, Trumbo opted to let his pistol do the talking. His first shot failed to get Wasson’s attention. But, taking cover behind a convenient pine, Trumbo fired off another in Wasson’s direction. The would-be settler promptly pulled out his own revolver and returned fire. And his aim was definitely better: he struck Trumbo squarely in the shoulder and right thigh. As luck would have it, Col. Reese’s teenage son was on hand and watched the drama unfold. Spotting his stricken brother-in-law, the lad drew his own horse pistol and, running up close to Wasson, dispatched a load of buckshot into his face and neck.

Wasson himself helped load the injured Trumbo onto his wagon and ferried him home. Trumbo, with a severed artery in his leg, was initially believed to be at death’s door, but managed to recover – though he carried a limp as a souvenir for the rest of his days. Wasson got to endure the painful ordeal of digging buckshot from his face, and an equally unpleasant hearing before a county Commissioner.

The “battle of the pine tree,” as one local called it, had been fueled by a simple misunderstanding. Yes, Reese had been the original owner of the entire stretch of land. But Reese had sold off 160 acres of it to Benjamin Sears, on condition that Sears erect a fence around both parcels. Wasson, in turn, had forked over $375 to Sears for the land. True, the deal between Sears and Wasson hadn’t yet been put on record when the fight broke out. And yes, Sears hadn’t quite completed his fencing obligation when he accepted Wasson’s money. But he’d made a good start, and Wasson had been prepared to finish the job.

They say all’s well that ends well, and the “Battle of the Pine Tree” ended without further bloodshed. Wasson, with an unimpeachable claim of self-defense, was never charged. He ensured that his deed from Sears got recorded the very next day, and followed it up with a formal survey two months later. Trumbo, for his part, had the good grace to admit he’d been wrong to start firing. History hasn’t quite tied up all the final details for us, but it’s a good bet that Reese’s much-promised fence got satisfactorily finished.

That remnant from the “battle of the pine tree” that’s still visible today? Well, it’s the small stone-and-wood house that Wasson built, which remains standing on the south side of Genoa Lane just east of town. (Though it took until April, 1864 before Wasson’s title was firmly upheld in court.)

As historian Bob Ellison points out, the stone house was a strongly-built structure, with its foundation dug below the frost line to prevent destabilizing frost-heaves. Larger stone blocks were carefully chinked with smaller stones, keeping mortar to a minimum. A single upper window allowed in a splash of daylight. It was such a strongly-built house that it served double-duty as Nevada’s first jail for a short time in 1860 (though as far as we know, only one man was imprisoned there — a man named Watkins accused of killing a purported horse thief).

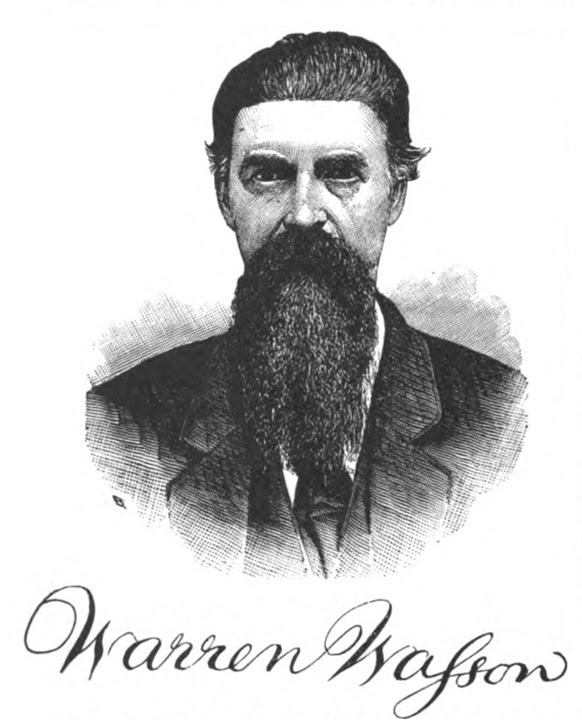

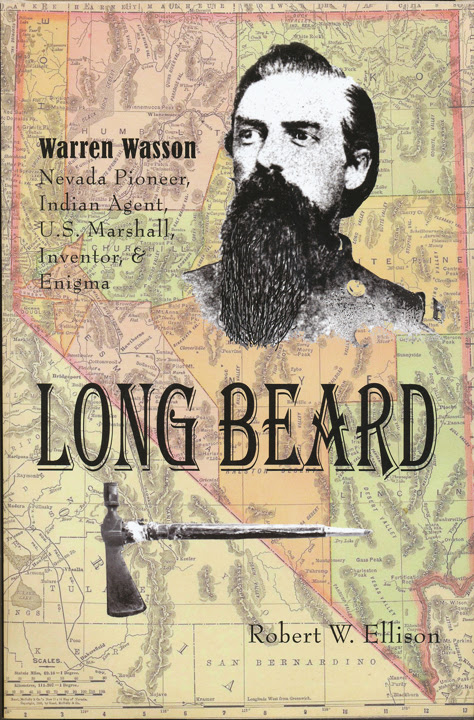

As for Warren Wasson himself – ah, that’s a separate tale of adventure. His life really does fill a book – and thankfully, Bob Ellison has written a terrific one. The short version: Wasson was born on Christmas Day, 1833 in Harpersville, New York. His family soon moved to Illinois, but when the Gold Rush struck Wasson and his father crossed the plains in 1849. Young Wasson was just sixteen at the time.

A couple more cross-country trips followed, plus a brief attempt to ranch in Long Valley (near Beckworth Pass). In 1858, Wasson sold his 1,280-acre ranch and moved to Genoa. He took part in the Convention to organize a provisional territorial government in July, 1859, and was appointed a Deputy U.S. Marshal by Judge Cradlebaugh the following September.

Over the years, Wasson developed warm relationships with both the Paiute and Washoe tribes. During the Indian Wars of 1860, he was pressed into service at various times as a courier, a scout, and an acting Indian agent, earning the nickname “Long Beard.” And that staunchly-built Genoa stone house? It became a refuge for women and children when the fears of an Indian uprising were at their height.

None other than Abraham Lincoln appointed Wasson a U.S. Marshal when Nevada Territory was formed; he also became a federal Assessor of Internal Revenue. In 1865, Wasson was appointed an Aide-de-Camp to Nevada Governor Henry Blaisdel, a position that carried with it the title of “Colonel.”

In May, 1867 Wasson married Grace Treadway of Carson City at a church in Virginia City. To provide a nicer home for his bride, Wasson erected a larger, frame house in front of his small stone house, turning the old stone building into a storage cellar. He and Grace would eventually have seven daughters and a son together.

The couple moved to Carson City after Wasson was appointed an Aide-de-Camp to the next governor in 1872. He sold his Genoa ranch to Herman Winkelman and stopped ranching altogether. But by April 1881, Wasson seems to have had enough of city life.

Just 48 years old, he may have been hankering for a few more adventures in life. Wasson left town, ostensibly headed for Walla Walla, Washington. If he ever made it there, he apparently kept right on going. Sadly, his wife and children never heard from him again.

Warren Wasson passed away in June, 1896, in Edwardsville, Kansas – leaving behind both a fascinating life and the fascinating mystery of what exactly he did in those last 15 years.

Wasson’s frame house is now gone; it was torn down in later years and the lumber re-used in other buildings around Genoa. But his old stone house-turned-cellar still stands, a silent reminder of a nearly-forgotten man.

____________________

Special thanks to Bob Ellison for his help with this story; any errors are solely my own. Copies of Bob Ellison’s marvelous Long Beard: Warren Wasson, Nevada Pioneer, Indian Agent, U.S. Marshal, Inventor & Enigma (Hot Springs Mountain Press 2008) are available from the Legislative Counsel Bureau bookshop: shop.leg.state.nv.us. For further reading about Warren Wasson, see Richard K. Allen, Tennessee Letters; and Thompson & West, History of Nevada (1881), p. 534.