I’m working on a third time-travel novella, set in 1887. And what a fun trip back in time it’s been, reading the old newspapers to capture the period flavor!

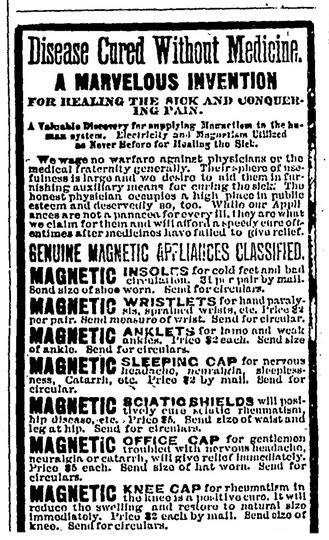

There were wonderful ads, of course, like Genoa barber David DeLong, who doubled as a dentist. And then there was this period gem:

But in addition to cool ads, the 1887 papers also contained real-life tales that grip your heart . . . like a story from April 1887 about a little four-year-old girl who nearly died from eating “poisonous parsnip.”

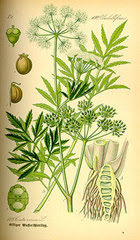

Seems the girl and her brother were playing in a Carson Valley water ditch when they stumbled across what looked like parsnip roots. The boy took a bite and pronounced it “bitter and not fit to eat.” But his younger sister swallowed a small quantity of the root, and quickly fell ill (likely experiencing convulsions).

The children’s father, Assemblyman H. Springmeyer, sent his oldest son on horseback to fetch Dr. Williams from Genoa, six miles away. But as the minute sticked by, the little girl grew worse. Panicked, her father dispatched a hired hand on a second horse, urging him to make “double quick time.” The hired man found the doctor, and the doctor whipped his buggy team to a gallop — arriving at the Springmeyer home “just in time” to save the little girl’s life.

Thank heavens there was a happy ending to that near-tragic true tale! But that story got my inquiring mind to thinking:

What the heck was “poisonous parsnip”? Well, a quick search suggests at least two good possibilities: water hemlock (Cicuta occidentalis or douglasii, one of North America’s most toxic plants); or poison hemlock (Conium maculatum, also toxic, as the name implies). There’s also wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa), a wild version of the common parsnip that’s edible. But which was the plant that poisoned this little girl in 1887? Just a guess, but the culprit likely was poison hemlock; its single root would have looked more like a parsnip to the children than forked-root water hemlock.

And what, exactly, would a Victorian doctor have done for a poisoning victim in 1887? I asked a physician-friend, who suggested ipecac might have been given to induce vomiting. Potassium bromide could also have been administered — an early anti-convulsant and sedative, it was first used to treat epilepsy in 1857. Then again, perhaps the child was simply among the lucky ones and recovered largely on her own, and the doctor simply got the credit.

It’s a cautionary tale that reminds us that childhood deaths were far more common in the “good” ol’ days, and that life-saving treatment might well depend on the speed of your horse.

If you’re fascinated by plant lore and early medicine, as I am, you might enjoy reading Captain’s Kidnapped Bride, in which the curative powers of herbs (Jamaican plants, this time) play a starring role!

____________

Special thanks to my retired-ER-physican friend for his insights on potassium bromide, ipecac, and early emergency medicine; and to my botanist friend for helping point a likely finger at poison hemlock!