“I do not believe in doctors,” quipped Brigham Young’s older brother, Joseph, in 1858. “I would rather call upon the Lord.”

It was a fairly common sentiment at the time, and for good reason: a wide variety of quacks were happily dispensing an equally wide variety of quack medicines.

There were “botanical” doctors; there were homeopathic physicians. There were traveling patent-medicine peddlers and newspaper ads confidently promoting “cure-all” remedies. In addition to ordinary physicians, there were “Thomsonian” doctors — followers of Samuel Thomson, a medical rebel who believed “restoring heat” was the trick for healing a patient. The harsh Thomson protocol applied an uncomfortable series of emetics, enemas and sweat baths, casually summarized as “Puke ‘em, sweat ‘em, and purge ‘em.”

Even mainstream practitioners back in the day were often dismissed by suspicious citizens as “Poison Doctors.” High doses of mercury and techniques like blood-letting were not unusual, and other quirky “remedies” seem outright bizarre by today’s standards.

Dr. Benjamin King approved the use of cow dung as a poultice to treat Hosea Grosch’s badly infected foot at Gold Hill in 1857, for example — a ministration that didn’t help and might have hastened Grosch’s demise. Even as late as 1892, a pneumonia sufferer in Virginia City was relieved of half a pint of his blood in a well-intended medical intervention. Ah Kee, a Botanical Physician with an office on Third Street in Carson City, claimed in his advertisements to have “cured many patients in town” — but there was also a Chinese section quietly located at Lone Mountain Cemetery.

The only ones who might have been happy about all these attempts at “curing” were the local undertakers, and those proliferated. Early practitioners of the mortuary arts in Carson Valley included M.A. Downey, George Kitzmeyer, and Samuel C. Wright.

Undertakers were evidently none too popular. Quipped the Reno Gazette Journalabout what they called the “disagreeable business”:

“[The undertaker] attends church and keenly surveys the faces of the congregation with a critical eye, . . . deftly tuck[ing] his business card under the door of the invalid. He is jolly when pneumonia gallops through a community, and howls with delight over a wholesale railroad accident. He can diagnose a case of physical degeneracy of any kind with unerring certainty at a distance of fifty feet. . . He knows the dimensions of every man in the community and the coffins he furnishes are always guaranteed to fit, so that the defunct customer can rest without danger of contracting chafes and bunions.” [Reno Gazette Journal, June 3, 1882].

One unfortunate who landed in the undertaker’s parlor, a victim of prevailing medical wisdom and probably also malpractice, was young Harrison Shrieves.

A Civil War veteran (he had enlisted in the 10th Ohio Cavalry when he was about 15), Shrieves moved west after the war and landed a plum job as a conductor on the V&T Railroad. Fate continued to smile on Shrieves for the next few years. Around 1870 he married Louise Tufly, daughter of George Tufly, wealthy proprietor of Carson City’s St. Charles Hotel (and later state Treasurer).

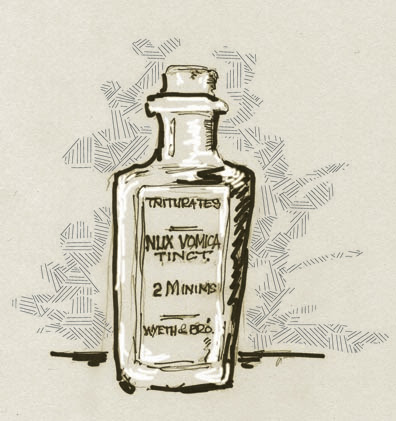

It wasn’t quite the “Ides of March” that got him, but it was close. Harrison Shrieves was given a well-intentioned dose of the homeopathic remedy “Nux Vomica” by Dr. Stephenson of Virginia City in 1873. Concocted from seeds containing strychnine, Nux Vomica was commonly used in dilute form to treat a wide range of illnesses from constipation and heartburn to flu. Harrison, however, was apparently given much too much. He suffered for months, and was just 28 when he finally succumbed on March 11, 1874 from his treatment. He is buried in Lone Mountain Cemetery.

There’s more about Shrieves, Tufly, Kitzmeyer, Wright and a great many other Carson Valley pioneers in my friend Cindy Southerland’s beautifully-illustrated book, Cemeteries of Carson City and Carson Valley (Arcadia Publishing 2010). Mark Twain himself commented that “to know a community, one must observe the style of its funerals and know what manner of men they bury with most ceremony,” as Southerland points out. This fascinating book highlights the final resting places of a wide variety of pioneers in this beautiful valley — from stagecoach drivers to governors, soldiers to desperados. Great photos and a helpful description of cemetery symbolism make this an uplifting and informative read. You can find it here through Amazon.com.

Another great book we wanted to mention, this one about early Nevada doctors and early medical remedies (including Chinese and Native American practices): The Healers of 19th-Century Nevada, by Anton P. Sohn (Univ. of Nevada, 1997). This one was a happy recent “find” for us at Morley’s Bookstore in Carson City, Nevada. If you haven’t been there, take time to stop in. Morley’s offers a fabulous assortment of local and Nevada history books plus a great “old-time bookstore” feel. Its 1864 brick building on West King Street is one of only four original stores still extant in Carson City. Be sure to check out the great historic photos on the wall showing this historic building’s evolution through time. Tell him we sent you.

Like to read more Sierra history stories like this when they come out? Sign up for our free history newsletter at the top right of this blog page!

greate article.. happy Doctors day