The sign on the tall, blue house in Virginia City caught our eye as we whizzed past one recent afternoon: “The Chapin House.” It’s an unusual last name — and one we recognized from old letters in Alpine County.

So, just who was Samuel A. Chapin? We tracked down a few pieces of his life story puzzle — and what a life he had!

Born in Northbridge, Massachusetts on September 2, 1811, Samuel Austin Chapin was the fifth of eight children of Henry and Abigail Chapin. His family moved to Michigan Territory in the spring of 1830, and Samuel’s early adulthood was spent in White Pigeon. He would later recount “startling and amusing” tales of “roughing it” there, and serving as sheriff of St. Joseph County, Michigan.

Samuel joined other Michigan volunteers during the Black Hawk War of 1832, quickly rising to the rank of Brigadier General with the Michigan State Militia. In 1840, he went on to serve as a member of the Michigan House of Representatives for one session.

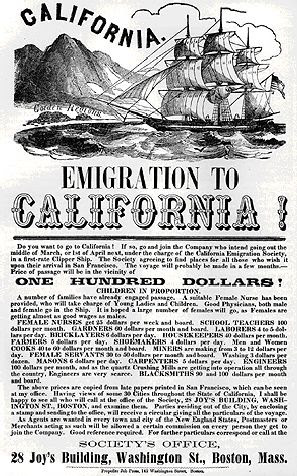

Exciting as all that must have been, nothing could quite rival the excitement of finding gold! Chapin eagerly joined some of the earliest Gold Rush crowds to California, though exactly when he arrived there is unclear. He once claimed to plainly remember the day that “we of ’49” arrived at San Francisco Bay. Other accounts, however, peg the actual date of his arrival as May 20, 1850. Even so, that date still puts him among the earliest eager argonauts.

Chapin’s adventurous journey included a “rough passage” aboard the vessel Empire City; a “raging fever” on the Chagres River; and an unexpected hiccup in Panama when the expected continuation vessel Sarah Sereds failed to arrive. Chapin and his companions managed to book substitute passage aboard the steamship Oregon for $500 a head — procuring a berth in steerage along with a thousand other eager travelers.

Once aboard ship again, Chapin was said to have “organized a mess” with fellow passengers William Smith, former governor of Virginia, and L.B. Benchley, of San Francisco — political connections that helped render the rest of his passage “comparatively comfortable.”

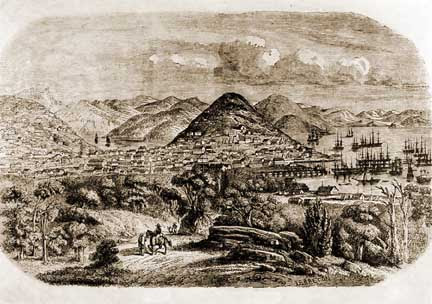

During his earliest days in California, Chapin operated a hardware business. He also managed to become a member of the San Francisco Board of Education, helping select property upon which to build future schools, and made friends with the influential editor of the Evening Bulletin.

By 1860 the Gold Rush had largely petered out — but the Silver Rush now was on! And once again, Chapin was in the forefront of adventurous pioneers.

Chapin acquired a mill site on the Carson River, four miles from Silver City, in July, 1860. That same month he had a survey done on land in Steamboat Valley — property that included not only a mill site but also valuable timber and water rights. And his political instincts evidently remained as sharp as ever; Chapin soon was tapped to serve as a member of the two Constitutional Conventions working to frame Nevada’s state constitution.

Naturally, Chapin had a finger in several early mining pies. He acquired an interest in the quartz mines of Mariposa County. His name appears in May, 1863 among the list of incorporators of the Buckeye No. 2 Gold & Silver Mine in Scandinavian Canyon (soon to become Alpine County). And he also acquired an interest in mines on the Comstock. In 1865, Chapin issued a “report” extolling the merits of his “Gold Hill Front Lodes” at Gold Hill, Nevada — two parallel claims happily situated between the Yellow Jacket and the Justice Mines. This “report” (actually a sales brochure) was, of course, heavily leavened with “affirmations and statements from various persons” about the value of these two mines.

Letters show that not all was sweetness and light in Chapin’s mining business, however. In 1869, Ahnarin B. Paul wrote Alpine County mine promoter O.F. Thornton: “I saw Chapin to-day — he can’t get the [ore-processing] settler to produce the electricity which must be had for precipitating the mercury.” And by 1872 Chapin was back in San Francisco, still trying to sell his mining claims. He wrote to Thornton offering a mining claim near Devil’s Gate for a hefty $100,000 (likely the same two Gold Hill Front lodes), touting his “great expectations” for the property. But his “Hope Mining Co.” at Silver City, he acknowledged, had recently become “embarrassed” and (as he put it) “went to the wall.”

Chapin’s stately 15-room house at 311 South “C” Street was constructed in 1862, during Virginia City’s mining heyday, and may originally have been built for him as a private residence. But by 1880, Chapin House had been converted into a boarding house, with a Mrs. Cavanaugh acting as the proprietor.

Meanwhile, back east, one of Chapin’s sisters had married a Wheaton, and was living in Norton, Massachusetts. Samuel was apparently her favorite brother. In 1884, Samuel and his wife retired and moved back to Massachusetts to live with the sister. There, he would serve as a Trustee of Wheaton College from 1889-1890.

By now 78 years old, Chapin conceived the notion of revisiting “scenes of his early life,” and eagerly joined a group of fellow pioneers for a trip back to California. It would be his last big adventure.

Chapin died suddenly of a heart attack while in San Bernardino, California on April 17, 1890. Stopping there with his fellow pioneers on their way to San Francisco, Chapin had just finished delivering a rousing address to the crowd at a reception. The last words to fall from his lips were: “God bless the noble State and the dear people of California!”

Chapin’s body was placed in an “elegant coffin,” said to be identical to the one in which General Grant had been buried. It lay in state briefly in San Bernardino, with solemnities conducted by the Native Sons of the Golden West and the San Bernardino Pioneers, before being loaded on a train for return to Boston. Both Chapin Hall at Wheaton College and Chapin Street in Alameda, California would later be named in his honor.

As for Chapin House, it continues to keep its silent vigil, looking down over the town of Virginia City from its lofty perch on “C” Street.

And here’s the last, fun snippet to this story: boardinghouse-keeper Mrs. Cavanaugh — or perhaps even Samuel himself — may not entirely have vacated the premises. Visitors have been said to “complain of an uneasy feeling,” as if there’s a ghost in the house!

_______________________

Like to read more silver mining history from the Comstock Era in nearby Alpine County?