Jonas Winchester was one of a kind . . . .

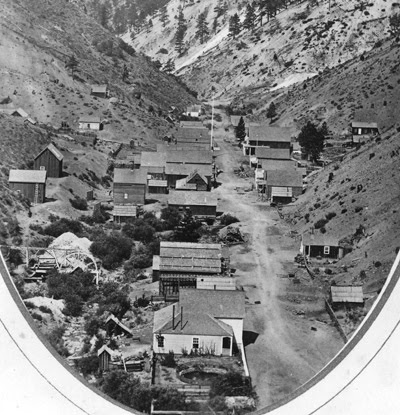

The year was 1871. Hope was in the air, in the tiny mining town of Monitor, California. “General” Jonas Winchester and his wife had recently arrived from back East. And word was that the Globe Gold & Silver Mine was finally going to be pushed in earnest.

The title of “General” appears to have been self-applied. Jonas had no military experience (at least none that we’ve been able to find). In addition to that confident title he also adopted an equally confident motto: “Push things.” And promote he did! Advertising flyers screamed about the Globe Mine’s prospects — its ores, they said, were “believed to be incalculable in quantity.” And best of all, they could supposedly be worked cheaply. Winchester assured investors he had “invested all his own fortune in the business,” and intended “to reside permanently at Monitor.”

But despite such bravado, things actually weren’t going terribly well for the Globe. It did have a mill, but the ore was yielding just $10 a ton. Its workmen being unpaid, both mill and mine were soon shut down. In April, 1871, Winchester candidly acknowledged to a fellow miner that there had been “too much coyoteing” going on. A family feud may have been part of the problem; Winchester complained bitterly about the “treachery” of a brother. The Globe’s mill had also barely escaped a devastating fire, he said, and there was a “need for re-organization of its finances.” Prospects were looking gloomy indeed.

By July, however, the mood had switched from gloomy to gleeful. A rich copper vein had just been struck in the Globe, and there was “every indication of a mammoth copper ledge” just ahead. Early assays produced up to $75 in copper and $20 in silver, and ore as rich as 36% copper was said to have been found in the deeper levels. That summer, Winchester also had one more cause for celebration: his third wife, Laura, presented him with a son on August 10, 1871, born there in Monitor.

Continuing the work on the mine, of course, required a continued influx of capital. Winchester put his best literary skills to work in an 1872 prospectus, teasing investors with fabulous statistics. Capitalization of the company was now a rich $650,000. Progress thus far included a 5.5 x 6.5-foot double-tracked tunnel, “nearly” 1,500 feet long (a shameless exaggeration, as later facts showed). Rail had been extended conveniently from the mine to an adjacent 45’ x 60’ mill, which was almost ready to work the ore. “When finished,” the mill should be able to crush 40 tons of ore a day. A 30-horsepower engine and boiler had already been purchased, and 500 cords of wood were on hand. Hoisting works had been erected, and the company’s claims crossed “some half dozen or more veins.” The promised return to those willing to invest? “25% per annum in gold.” How could you go wrong?!

By fall, the Globe again found itself unable to pay its bills. But Winchester’s glowing advertising evidently did the trick. Frank Winchester (a son by Jonas’s first marriage) arrived in Monitor in October with enough cash in hand to pay off the debts of the Globe. And, as an added sign of confidence, Frank signed a contract to extend the tunnel another 100 feet. Frank quickly departed for the East again, but his father, “General” Winchester, remained behind at Monitor as mine superintendent.

Winchester may have been a terrific mine promoter, but he’d apparently had little experience running a silver mine before. What he lacked in practical know-how, however, he made up for with sheer bravado. And on top of his naturally boisterous personality, Winchester was a firm believer in Spiritualism. He firmly believed that he had been personally chosen by the “Ancients” to run the Globe, and that the spirits would guide him to make the mine a success.

Spiritualism was a quasi-religious movement that depended on mediums to communicate messages from the spirit world to convey wisdom to the living. Seances and “table-rapping” sessions were in great vogue in the 1860s and ’70s. Even newspapers in such remote outposts as Silver Mountain and Monitor carried advertisements like those of “Madame Remington” and “Madame E.F. Thornton,” promising to send readers a picture of the “very features of the person you are to marry” — for a mere 50 cents, remitted to the medium by mail.

Winchester, a firm believer in Spiritualism, was convinced that a band of “Ancients” could speak to him through mediums. The leader of this spiritual band was supposedly an Atlantean named Yermah, while Yermah’s wife was the towering six-foot “Queen” Azelia. Winchester went so far as to name his newborn son Yermah, and a subsequent daughter, born in September, 1873, after the spirit Queen.

Winchester wasn’t alone as a devotee of Spiritualism in early Monitor. Fellow resident O.F. Thornton (no relation to the clairvoyant) corresponded regularly with both psychics and fellow Spiritualists, including one William H. Sterling. “The Spirit World is on our side, and they will take care to bring us success at the right time,” Sterling assured Thornton in one letter in September 1871. Meanwhile, Spiritualism may also have had a practical application. Sterling confided to Thornton that he was using “Spiritual topics” to persuade an investor to sink money into Thornton’s Good Hope mine.

The opportunity for profit from this connection with the “Ancients” was not lost on Winchester, either. In early 1871, he reached out to acquire rights to a set of “spirit pictures” drawn by a pair of San Francisco mediums while in a trance. There was profit potential in selling the images, he was convinced.

Despite the helpful advice of the “Ancients,” Winchester’s stewardship of the Globe was roundly criticized. One aggrieved investor concluded that Winchester’s “reckless and incompetent manner of doing business would prevent forever any success, no matter how rich or extensive the mine should prove.” Winchester was simply a “reckless spendthrift,” he added, notwithstanding supposed selection “by the Ancients as the only man in the world” for the job.

Winchester did manage to push the Globe’s tunnel some 1,000 feet into the mountain, with several side-drifts. A steam furnace and boiler were installed in a separate building at the mouth of the tunnel, and the steam conducted in insulated pipes to an engine and pump located in an underground chamber. Marketing genius that he was, Winchester also had a series of beautifully-detailed photographs taken of the mine and surrounding settlement to help induce investors to continue to float the operation.

Despite the massive work done on the mine, the Globe’s stout 4” Cornish pump eventually proved unable to keep up with water flowing in. The boiler’s steam capacity also proved insufficient to work the pump and the hoist. By the end of 1873, work at the Globe was abandoned. As one mining report concluded, the mine’s sad history had been one of “difficulties, delays, expenses, and disappointments.”

Winchester and his family finally shook the dust of Monitor from their feet in November, 1873, and moved west to San Francisco. He brought along his “well-magnetized desk” to their new abode (perhaps magnetism helped the spirits to focus). Soon he was hawking those “spirit pictures” he’d acquired in a new “Spirit Art Gallery.” Winchester managed to bring in about $6 a day from his gallery, at least for a time — enough to cover costs, though not enough to afford him a salary. Ever upbeat, he claimed to a friend he was simply happy to “re-enter upon civilized life.”

Winchester’s Spirit Gallery featured reproductions of pencil portraits of 28 of the “prehistoric and ancient spirits.” These included “Yermah” and other natives of Atlantis from 16,000 years ago, plus the “progenitors of the Mississippi mound builders, and the architects of the lost cities of Central America. In case you’d never heard of Atlaneans, there was also Confucius, Gautama, Jesus, and Mother Mary. Included in the mix was a “Hindoo Necromancer and Alchemist” from 8,000 years ago who, by the way, had discovered the Elixer of Life. Not to be overlooked: a Magician priest from Ancient Ninevah, and another learned Egyptian from the time of Moses. Visitors to the Spirit Gallery could acquire a photographic reproduction of these sketches: just 50 cents for a card-size picture or $1 for a larger cabinet card. Such a deal.

A solicitation for subscribers penned by Winchester in 1874 promised that the “locked-up knowledge of prehistoric ages” would soon be opened, thanks to the “lost arts and occult powers” of the ancients communicated through “highly-developed” mediums. “Let a cordial welcome be given to these ancient spirits,” he wrote, who come “offering the priceless boon of knowledge.” The spirits were prepared to share “an outpouring of ancient lore which will bless mortals and point the way to an era of brotherhood which shall no longer be a dream of Utopia but a living reality.”

“Priceless” that ancient wisdom may have been. But the spirit pictures proved a commercial dud. In May, 1874, the local press in Monitor noted Winchester’s current “financial impecuniosity, resulting from his late adventure in the ‘spirit picture’ business.”

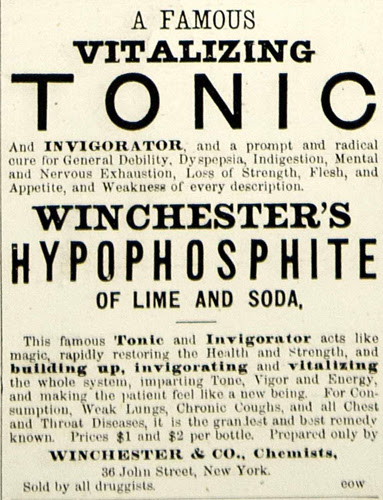

Perhaps aware of the benefit of diversifying, Winchester had his finger in more than one entrepreneurial pie about this time. In addition to the spirit picture business, he also was engaged in selling a patent medicine, under the catchy title of Winchester’s Hypophosphite. His own signature was prominently featured on the label.

Winchester’s patent medicine was hardly a novel idea, but it made use of all the recognized ingredients for snake-oil-style success. As one tongue-in-cheek article advised readers in 1872, the “Recipe for Getting Rich” from a patent medicine was:

Eventually, Jonas Winchester took up “fruit-growing” near Columbia, California. And on February 3, 1887, the wild and crazy life of Jonas Winchester finally came to an end. He was 76 years old. His obituary described him — accurately — as energetic, warm-hearted, and a man of high intelligence. He was laid to rest in the Odd Fellows graveyard at Columbia, Tuolumne County, California.

As for Winchester’s family, his obituary reported that in keeping with Winchester’s own Spiritualist views, the family “rejoice in the assurance that the dear patriarch still watches over the loved of home, and will see that no evil attends their footsteps.”

_______

So, just how did Jonas Winchester manage to get to Monitor in the first place? Ah, that’s a wild and crazy story in itself! Tune in next time for the rest of Jonas Winchester’s amazing story!

_______

Copyright K. Dustman 2019

[…] a story in itself! (And if you missed Part 1 of Winchester’s wild and crazy story, here’s where to read […]