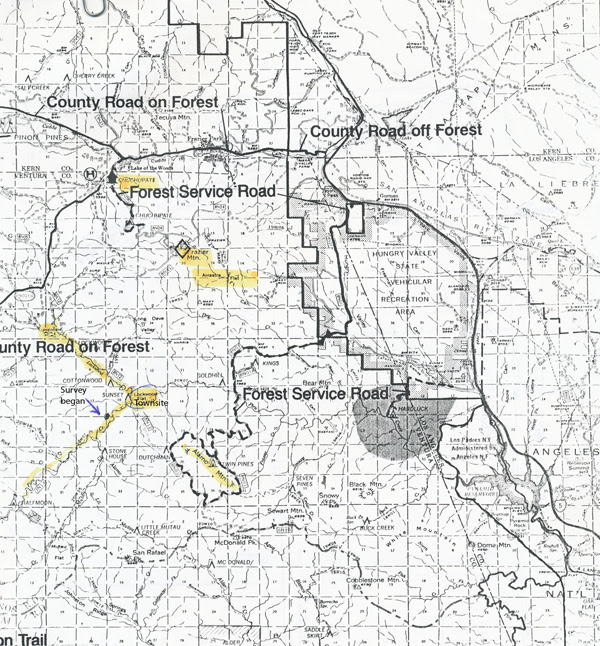

It was a couple of weeks before Christmas, 1886 – December 3rd, to be exact. “Colonel” Alonzo Winfield Scott Smith was out exploring the back country of eastern ![]() Ventura County, near the confluence of Piru and Lockwood Creeks.

Ventura County, near the confluence of Piru and Lockwood Creeks.

And some might say it was a Christmas miracle: Voilà! Smith stumbled across a “lost” gold mine. Or maybe it was a silver mine. Maybe it was both.

In any event, as Col. Smith gleefully told the tale, this “lost” (now found) mine had been dug by the Spanish padres. The mine’s entrance (he said) was cleverly concealed, hidden by cottonwoods deliberately planted to hide the tunnel’s mouth. Bolstering the seriousness of his discovery (so he claimed) were remnants of an old mining smelter. And for those who might still be dubious, Smith turned up a “silver brick” – or, as later stories would describe it, a one-pound “ancient Jesuit silver spike.” (Spikes made out silver? Well, who knows. Perhaps silver spikes were a “thing” back then.)

The Piru Mining District, where Smith claimed to have made these astonishing discoveries, had long been the focus of “lost mine” tales. There were indeed rumors, even before Smith, that the Spanish padres once mined there. Assorted tales were spun about an elderly Native American named Tecuya who’d worked in the mine for the padres and supposedly spilled pieces of the tale – despite a vow of secrecy and a deadly curse on anyone who shared the mine’s location. Some described ingots stacked up like cordwood. An unnamed prospector once arrived at Fort Tejon (it was said) with a “sack” full of gold. How could you not love such fables?!

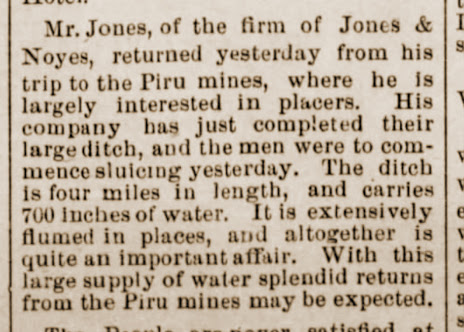

Long before Col. Smith put in his appearance, traces of placer gold actually had been found in the Piru Creek area. Some sources even claimed gold was found at Piru 11 years earlier than John Marshall’s famous mill-race discovery! In 1871, a good 15 years before Smith wandered out there, a heap of ore at Piru was thought to include both silver and gold – though a later investigation debunked the report. Apparently there was enough substance to the rumors of placer gold, however, that a four-mile ditch was completed in May, 1876 to bring water to would-be Piru miners.

And then Col. Smith arrived on the scene in the winter of 1886. Some described Col. Smith as “affable”; the Kern County Echo (perhaps a bit more honestly) called him a “queer character.” But Smith was just the type you’d expect to be intrigued by “lost mine” tales.

“[T]horoughly conversant with the mines of Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado,” as one newspaper put it, Smith claimed he hade 14 years of mining experience under his belt. His previous mining travels reportedly had taken him as far north as Alaska and as far south as Mexico, Chile, and Peru. In addition to whatever mining chops he may have accrued, Smith may also have picked up tips for a mining scam or two. As recently as June, 1886 (less than six months before his miraculous mine “discovery” at Piru), A.W. Smith “of Campo” was exhibiting a sample of ore from a newly-discovered mine in San Diego – one which Smith’s buddy enthusiastically claimed “will astonish the unbelievers.”

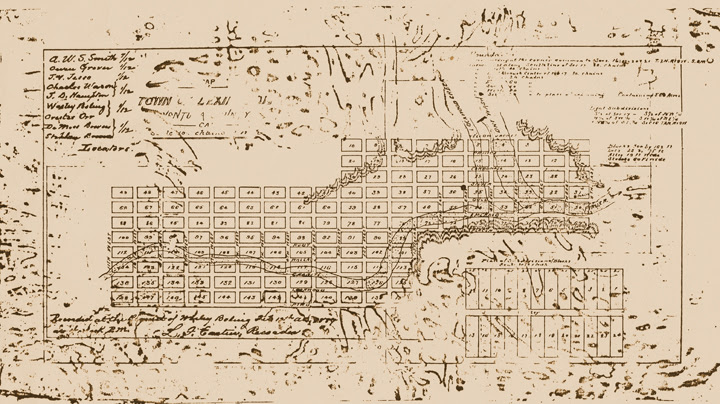

Following the happy December discovery of his latest “lost” mine at Piru, Smith rushed to file five mining claims. These included the Exchange; the Esperanza (Spanish for “hope”); and the Matchless (according to Smith, the “mother lead of the world”). News of the find traveled quickly. By February 7, 1887, there were already 150 men in camp. Soon, Santa Maria surveyor J.V. Jesse was busily engaged in laying out an entire town there at Lockwood Flat, to be known as “Lexington.”

Thanks to the surveyor’s work, some 148 blocks were created – on paper, at least. Each block measured 300 x 162 feet, and included 24 individual building lots, each 25 x 75 feet. Newly-arriving miners could secure a town lot for $10 — or $15 for a more desireable corner lot.

That probably sounded pretty appealing, at the time. The new townsite of Lexington was a “wild and beautiful” place and, except for its remoteness, offered a good spot to build. The ground here was nearly level. And the waters of the creek were conveniently just 50 feet away. A few log cabins were thrown up. Other miners took up residence in tents or simply slept out under the stars.

Early newspaper reports helped fan the initial mining excitement. Ventura’s Free Press reported enthusiastically on March 17 that the Exchange claim was “bigger than the Comstock and possibly as rich.” Perhaps not surprisingly, DeMoss Bowers, son of the Free Press‘s publisher, was a part-owner in the Lexington townsite.

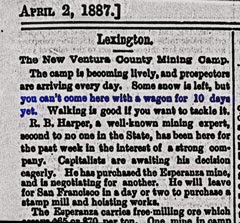

By late March, a log store was under construction, and a restaurant and boarding house were being planned. By mid-April, hoisting machinery had been purchased for the Esperanza, and a 50-stamp mill and a sawmill were predicted soon. A small arrastra was built of upright logs and a crossbeam, driven by mule-power. “Well-known mining expert” R.B. Harper purchased the Esperanza, and was said to be in negotiations to acquire a second mine as well. Soon even more miners had heard the exciting news. “The camp is becoming lively, and prospectors are arriving every day,” noted the Mining & Scientific Press in early April.

The Brown claim boasted a 75-foot tunnel and a 68-foot shaft. The Golconda, a 30-foot vein of silver and gold, had its own tunnel stretching 150 feet. The General Lee, Double Standard, Smith & Grover, Exchange, and Matchless were also making progress. A miner named Newton Nunn claimed to have located a quartz vein three feet thick, and rich in free gold. And those were just the hardrock claims.

Men engaged in placer mining were said to be pulling out $5 per day per man. Nuggets worth from $5 to $100 reportedly had been found.

For those eager to join the rush to Lexington, the trip from Ventura took three days by wagon. Directions were helpfully provided by the newspaper, as follows:

Or, if you preferred to arrive by “trail” (which presumably meant on foot or astride a horse or mule), you could take the Matilija Trail to “Mart[in] Beekman’s, and the next day to Lexington by [way of] Samuel Snedden’s.”

By early April a new wagon road had been opened from Gorman’s Station to Lexington. But even that route was only “passably fair” at first. Wagons remained impractical through the early spring as long as snow lay on the ground. But walking was still possible.

With the snow finally melted, things at Lexington became livelier than ever by May, 1887. Enough would-be miners had arrived that formal miners’ meeting was called for May 8th. A newspaper correspondent was living on site (presumably DeMoss Bowers, whose father published the Ventura Free Press). A post office was said to be planned.

Eager for publicity, promoters shipped off a sample of ore in early July to the offices of the L.A. Times for inspection.

But by summer’s end, 1887, interest in Lexington’s mines was waning. Well, all except for DeMoss Bowers. Still a believer in the mines’ potential, Bowers purchased the Carbonate Prince, Carbonate Queen, Carbonate King, and Matchless claims plus a mill site and five acres of land from Alonzo Smith on September 24, 1887, for real money: $12,500. About this same time, Smith had “just concluded negotiations” with an English syndicate to sell the Exchange claim for a whopping $60,000.

On October 6, two weeks after the sale to the ever-hopeful Bowers, the L.A. Times reported: “Lexington is dead; not a man in it.” Even the usual “bar-room mining” had ceased.

The trouble? The news column put it down to “that pile of rock brought down to Los Angeles.” The “rich sample” they’d sent to the Times apparently wasn’t quite so rich, after all. And before long, the town of Lexington itself had disappeared.

So what became of Col. Smith? Well, he didn’t hang around long, either. By October, 1887, Smith had left the wilds of Ventura County and was snugly ensconced in the far more comfortable digs of the St. Charles Hotel in Los Angeles. Remember, he’d just raked in at least $12,500 – possibly $72,500 if his deal with the “English syndicate” actually went through. Either way, he was sitting pretty.

The year 1892 found Smith in Utah, working as manager for a mining company and doing what he did best: rounding up investors. And by November, 1894 he was in Reno, touting a “rich ore discovery” in a “new district” south of Eureka.

But there the trail of Col. Alonzo Winfield Scott Smith goes cold. Someone named “Al.” Smith passed away in January, 1898 and was buried in the Odd Fellows Cemetery at Fresno. But so far we’ve found nothing that would confirm this was our Col. Smith.

The “Lost Padres” mine itself dropped out of sight again. For a while, at least.

Then in January, 1915, a Bakersfield paper reported two gentlemen had shown up in town with an “old Spanish map” pointing the way to an old silver mine located somewhere in the San Emigdio district. Wrapped first in silk and then buckskin, encased in a tin, and finally snugged into a protective cover of rawhide, the tantalizing map bore the date 1828. The two gents claimed it once belonged to a great-grandmother – and of course it was for sale.

The world is never short on willing believers. So this “ancient” map was purchased by three hopeful Bakersfield treasure-hunters for $500 – and that was pretty much the end of that fool’s errand.

And now, before you dismiss the legend of the Lost Padres Mine as total bunkum, consider this: In May 1976, a writer for the Mountain Enterprise newspaper claimed she personally had seen a tarnished silver ingot, presented for her inspection “a few years ago” by a stranger named Ben Clark. A metal detecting buff, Clark claimed the bar was just one of 29 silver ingots he’d found in a hollow tree near – yes, Lockwood Flat, the former site of Lexington. Stamped on each bar was the image of a lamb carrying a banner – said to be the mark of an asistencia (extension) of the San Emigdio Mission.

So, who knows. Perhaps the good padres really did once have a silver mine in Piru. Maybe, just maybe, Col. Alonzo Smith was onto something.

Enjoyed this story? Hope you’ll sign up for our history newsletter (it’s free!) Stories come out every 3 weeks or so. Just find the sign-up box right on this page.