A Short History of Lebec (Part 1):

Peter Lebec may have lost his battle with a grizzly bear almost 200 years ago. But Lebec’s name still graces the California valley where he died in 1837.

Today, the small town of Lebec, California – named after the unlucky Peter — is a bedroom community nestled beside Interstate 5, on the route between Los Angeles and Bakersfield. But just who was Peter Lebec, and what brought him to the mountains in the first place?

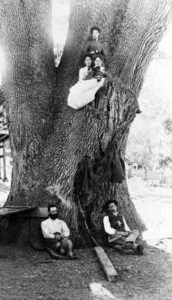

Much of the details of Lebec’s life have been lost to time. But here’s what we do know for sure: Peter Lebec died October 18, 1837. His friends interred his body beneath a towering white oak tree near where he died, then shaved a large, flat space on the trunk and carved a memorial to the fallen man:

I.H.S.

Peter Lebec

Killed by a X Bear

Oct’r 18, 1837

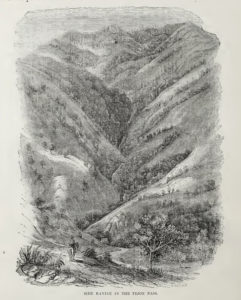

Although the area was remote and unsettled at the time, Peter’s epitaph still managed to attract the attention of a few passers-by. Five years after his tragic death, an unnamed traveler stumbled across the inscription. And five years after that, the lettering on the tree caught the attention of members of the Mormon Battalion, who passed through the meadow July 31, 1847 on their way to Sacramento. At least three of Battalion members remarked on the inscription in their diaries. One, Henry Bigler, also recorded seeing the “skull and bleached bones” of a grizzly nearby.

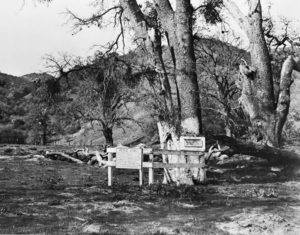

The tree continued its lonely vigil for another six years, until Lt. R.S. Williamson’s survey crew stumbled across it in September, 1853. The party also noted an “unusually large number of grizzly bears” in the well-watered meadow.

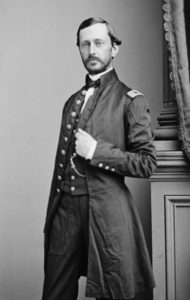

The following summer, prominent land-owner Edward F. Beale and his friends spotted the inscription on the tree on June 5, 1854. Luckily, newspaper editor William A. Wallace of the Los Angeles Star happened to be along. The tree’s bark was already starting to cover the writing, Wallace tells us, with the inscription now “some four inches within the bark.” Two rocks and a “slight elevation of earth” also marked the unfortunate Peter’s grave.

That same summer, the U.S. Army began constructing Fort Tejon in the meadow, with an advance party arriving August 10, 1854. The prominent oak tree now became the north corner of the Fort’s parade ground, and an adobe hospital was soon built close by.

Luckily for us, the fort’s physician, Dr. William Edgar, was curious enough about the inscription to ask local Indians what they knew about the story. They shared the only known contemporary account of how Peter Lebec met his dreadful end, reporting that Lebec had chased a large grizzly and shot it, then went up to the body, thinking the bear was dead — only to discover his mistake too late.

Fort Tejon was closed in 1864, and two and a half decades rolled by after that. But General Beale, for one, had not forgotten the tree. In April, 1888, at a banquet in his honor, the ever-forward-looking Gen. Beale described a plan to plat a town of “villa lots” to be named ‘Lebecque,’ after the mysterious Peter. And that was the beginning of the town of Lebec, if only in Beale’s imagination.

The following summer, 1889, a group of naturalists known as the “Foxtail Rangers” camped at the site of old Ft. Tejon for two weeks, enjoying the great outdoors. By now, the 50-year-old inscription was completely covered with regrown bark. But teacher Ella Houghton of Bakersfield became intrigued by the scar. Sticking her fingers under the bark, she thought she detected letters. And sure enough, when the bark was removed, the inscription came to light once again.

With Beale’s blessing, the Foxtail Rangers paid another visit to the tree the next July (1890), this time armed with shovels. Their mission: to see if a body really was buried there. Sure enough, some four feet beneath the surface, these amateur archaeologists discovered a skeleton – well, a partial skeleton. Its right forearm, both feet, and left hand were missing. After snapping a few pictures, the group reverently covered poor Peter’s mortal remains again.

Decades more slipped by without any further clues about Peter Lebec. Then in October, 1916 an earthquake struck, which damaging some of Ft. Tejon’s old adobe structures. As the buildings were repaired, broken adobe bricks were removed and thrown into a rubbish heap. And then one day, Tejon sheepman Samuel P. Allen happened to be poking around at the pile of disintegrating adobe when he saw something glitter.

That “something” turned out to be a silver five-franc coin, dated 1833. Nobody knows for sure where it came from, of course. But speculation immediately erupted that it might have fallen out of Peter Lebec’s pocket during his fatal battle with the bear, then been scooped up in the adobe mud when the fort was built. (The coin was reportedly given to a museum in Los Angeles in 1917.)

The Indians’ description of how Peter Lebec met his sad end seems to match the details given in the inscription. The mention of an “X” bear refers to the distinctive cross-shaped coloration along a grizzly’s shoulders and back. And this was clearly grizzly territory, back then.

But who was the unlucky Peter? Well, until about forty ago, there was sadly little evidence. A colorful story in the Bakersfield Morning Echo in May, 1921 claimed “Pierre LeBecque” was a French lieutenant in Napoleon’s army. In this rendition, Peter came to America to prepare a new home for Napoleon, should the emperor manage to escape his banishment. It was a fanciful tale that deserved an “A” for creativity, if an “F” for credibility.

Later historians speculated that Lebec was a French-Canadian trapper — perhaps a member of Michael La Framboise’s expedition, which was known to have left Ft. Vancouver in August, 1837. But subsequent research by Walt Wheelock and others confirmed that no Hudson’s Bay party ventured this far south that fall. And nobody named “Lebec” (or anything close) was found in the Hudson Bay Company records.

Instead, Wheelock believes Lebec was actually part of a roving band of “freebooters” – fur trappers and itinerant horse thieves known as Chaguanosos, led by French Canadian Jean-Baptiste Chalifoux. As Alta (Northern) California troops began moving south, this band of mercenaries agreed to help defend the Southern Californians, and in exchange won permission to hunt beaver in the mountains.

The Chaguanosos were certainly in the region about the time of Peter Lebec’s demise. In October, 1837, the group raided Mission Santa Ynez (north of Santa Barbara), where they stole horses. And in November, 1837 they descended on Mission San Louis Obispo, making off with some 1,500 animals, which they drove to New Mexico the following spring.

So, was the quiet small town of Lebec named after a “freebooter” and horse thief? Quite possible.

Still, Peter Lebec’s friends clearly loved him. They lingered to give him a decent burial, and carved an epitaph so enduring that the passing of their comrade is still remembered, almost two centuries later.